World #3 – Japan challenges China with sub exercise

Tuesday's World Events — Posted on September 18, 2018

(by Chieko Tsuneoka and Peter Landers, The Wall Street Journal) TOKYO – Japan sent a submarine to join three destroyers in an exercise in anti-submarine warfare in the South China Sea, strengthening the resistance by U.S. allies to China’s military expansion.

The submarine, the Kuroshio, joined the warships on Thursday before heading for a port call at the Vietnamese naval base in Cam Ranh Bay, the first such visit by a Japanese submarine, Japan’s Defense Ministry said.

The statement was the first public disclosure by the ministry of a submarine exercise in the South China Sea.

“It’s part of a strategic message that Japan would like to send to China and the countries in the region,” said Narushige Michishita, a professor specializing in international security at the National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies in Tokyo. “It’s a demonstration of Japan’s will to maintain a balance of power.”

Mr. Michishita called it “very significant” that Japan was practicing its anti-submarine warfare capability because China operates nuclear-powered submarines that can fire ballistic missiles.

The exercise followed operations in the region by British and French forces and repeated moves by the U.S. Navy to reinforce freedom of navigation in the South China Sea.

By visiting Vietnam, the Japanese submarine also highlighted the cooperation that the U.S. and its allies have been building with Hanoi, which contests China’s claims to some South China Sea territory.

Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Geng Shuang, asked about the Japanese submarine exercise at a press briefing, didn’t directly criticize Tokyo but said countries outside the South China Sea region “should act cautiously and avoid harming regional peace and stability.”

Mr. Geng said the situation in the South China Sea was improving and China was committed to working with Southeast Asian nations to resolve disputes.

The Japanese exercise could complicate the recent improvement in relations between Tokyo and Beijing, which has developed in part because both are facing tariffs on their exports imposed by the Trump administration.

Prime Minister Shinzo Abe met Chinese President Xi Jinping this month at an economic conference in Russia and said he would visit Beijing in October.

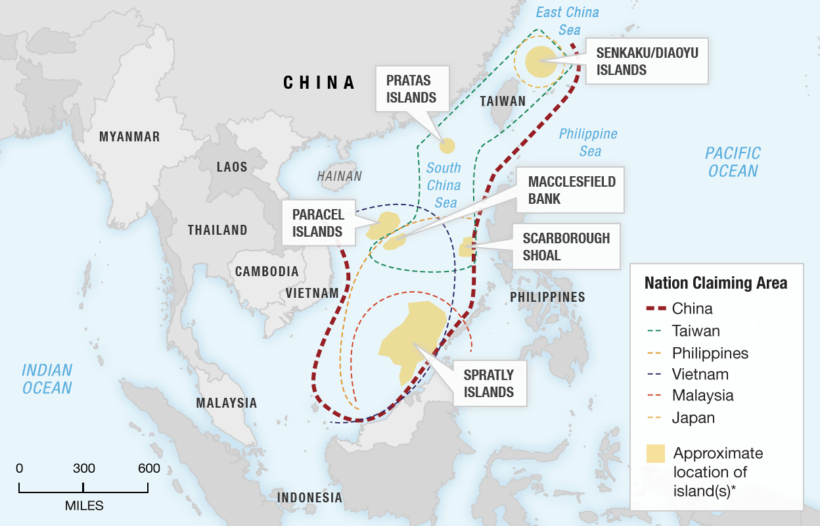

China has been stepping up its military presence in the South China Sea for years by building artificial islands on reefs and installing missiles and radar equipment at its bases. In May, China’s air force said it had landed a heavy bomber on a disputed island, bolstering its control of the area.

As much as a third of global trade passes annually through the 1.35 million square miles of ocean, which is also thought to be rich in natural resources including oil and natural gas. China says it has historical claims to almost the entire area and that it has the right to defend those claims.

In response, the U.S. and its allies have been boosting their own military presence in the South China Sea. A U.S. official said in May that two U.S. warships came within 12 nautical miles of Chinese-claimed islands. Beijing at the time warned Washington to stop “provocative actions that violate Chinese sovereignty.”

A British warship, the HMS Albion, took similar action on Aug. 31 near Chinese-claimed islands and drew a similar response. French warships have also sailed through the area this year. …

—Jeremy Page and Dominique Fong in Beijing contributed to this article.

Published at The Wall Street Journal on September 17, 2018.

Background

From the WSJ article above:

Japan’s challenge to China in the South China Sea is part of the two nations’ jockeying for advantage in the Pacific.

China has repeatedly used ships and planes to challenge Japan’s sovereignty over a group of islets in the East China Sea known as the Senkakus in Japanese and Diaoyu in Chinese. In January, Japan summoned China’s ambassador to protest what it said was an incursion by a Chinese submarine into the contiguous zone around the islands, which are controlled by Japan.

Japan scrambles its air force hundreds of times each year to respond to flights by Chinese military planes in the East China Sea. The number of scrambles involving China was 500 in the year ended March 2018, down from 851 a year earlier, according to the Defense Ministry.

The presence of Japanese submarines in the South China Sea would be displeasing to China, said Yoji Koda, a retired vice admiral in Japan’s navy. “Submarines are more difficult to detect than surface warships, so it is more unwelcome than surface warships’ entry to the waters,” he said.