News from Nepal, Eritrea and Estonia

Tuesday's World Events — Posted on April 28, 2015

Nepal was devastated by a magnitude 7.8 earthquake on Saturday, which originated outside the capital Kathmandu and has been followed by a series of powerful aftershocks. More than 4,000 people have been killed by the disaster.

Saturday’s quake was many times more powerful than the 7.0 quake that ruined Haiti in 2010. Nepal’s worst recorded earthquake in 1934 measured 8.0 and all but destroyed much of the country’s large cities.

The devastating 7.8 magnitude earthquake that violently shook Nepal on Saturday left more than human casualties in its wake. The country also saw a number of its iconic UNESCO World Heritage sites and most popular tourist attractions — some dating more than 1,700 years — reduced to piles of rubble.

Among the well-known Kathmandu landmarks destroyed by the quake was the 100-foot Dharahara Tower, which was cut down to a 30-foot pile of jagged brick, according to Reuters. Open to visitors for the past decade, as many as 200 people were inside the nine-story tower when it toppled, a police officer told Reuters.

The Kathmandu Valley includes seven groups of monuments that showcase a range of religious and artistic Hindu and Buddhist traditions that have made the area world famous, according UNESCO. Among the most well-known are tiered temples made of fired brick and timber.

Kathmandu’s three ‘Durbar Squares’ the courtyards outside the city’s old royal palaces, were devastated by the earthquake, with historic temples razed to the ground by the shocks. In the largest, known as the Kathmandu Durbar Square, rubble was piled up today after a large stepped temple was obliterated in the quake.

Images of the Durbar Squares in Patan and Bhaktapur, on the outskirts of Kathmandu, were also devastated by the shocks.

A side-by-side look at Kathmandu ‘s landmark Bhimsen tower, before and after it was damaged in Saturday’s earthquake in Kathmandu, Nepal. (Photo: AP)

The streets of Bhaktapur were impassable because of the rubble which lay several feet deep, with fragments of religious sculptures among the stonework on the ground.

In Patan, a temple had its tower broken in half, while the square was strewn with bricks.

In the hours after the quake, rescuers picked through the rubble of historic structures around the region, including ancient wooden Hindu temples, according to Reuters.

Nepal is famous as the world’s only Hindu Kingdom.

ERITREA: Escape from modern-day Sparta

Pictured as she was rescued from a stricken boat off the Greek island of Rhodes, the terrified face of Wegasi Nebiat last week became the symbol of Europe’s migration crisis.

A man rescues Wegasi Nebiat from the Aegean sea (AP)

The 24-year-old was among more than 100 migrants on a rickety craft that capsized en route from Turkey, drowning three of its occupants. But images of her being plucked to safety by a burly Greek rescuer have also put the spotlight on her homeland of Eritrea – a harsh, brutal dictatorship dubbed “Africa’s North Korea.”

The tiny Horn of Africa nation, which won independence in 1993 after a 30-year civil war with Ethiopia, is run as a one-party state by former guerrilla leader Isaias Afwerki and his cronies. Thousands of political prisoners languish in jail, no elections have been held in 20 years, and like Kim Jong-un’s hermit regime in Pyongyang, the country is off limits to foreign media and human rights groups.

However, one thing that Eritrea’s closed, secretive government cannot hide is how its population of just six million is now among the biggest customers of the people traffickers of the Mediterranean. The UN High Commissioner for Refugees says that of the 200,000 migrants who made the crossing last year, some 18 per cent, or nearly one in five, were Eritreans like Ms Nebiat. Only refugees from Syria, with its brutal civil war, made up more at 31 per cent.

An estimated 305,000 Eritreans, or five per cent of the population, have now left the country, fleeing torture, a stagnant economy, and conscription into a vast standing army that often amounts to little more than slavery. …

So why has Eritrea become the place where no-one wants to live? Unlike the Somalis, Nigerians, and Afghans with whom they often share their people smuggling boats, the Eritreans are not fleeing civil war or Islamic terrorism, or even particularly abject poverty. Indeed, many in the West would struggle to even find Eritrea on a map, never mind put it on a list of pariah states.

As with many of the world’s current conflicts, the story has its roots in borders drafted by Europeans a century ago, when Italy annexed Eritrea from the rest of Ethiopia during the colonial “Scramble for Africa.” The move deprived landlocked Ethiopia of its only port on the Red Sea, and when Addis Ababa sought to regain it in the post-war era, the ensuing conflict claimed around 200,000 lives.

However, while Eritrea emerged triumphant from the David and Goliath conflict, yesterday’s freedom fighters have become today’s despots. Like Robert Mugabe of Zimbabwe and Libya’s late Colonel Gaddafi, Mr Afwerki is accused of turning the country into a giant prison.

“During the 30 years war, even Eritrea’s enemies admired them, they were well organized and disciplined people,” said Professor Gaim Kibreab, an Eritrean himself and Professor of Refugee Studies at London’s South Bank University. “But after they took over power, they seem to have lost their way, the president has become very dominant.”

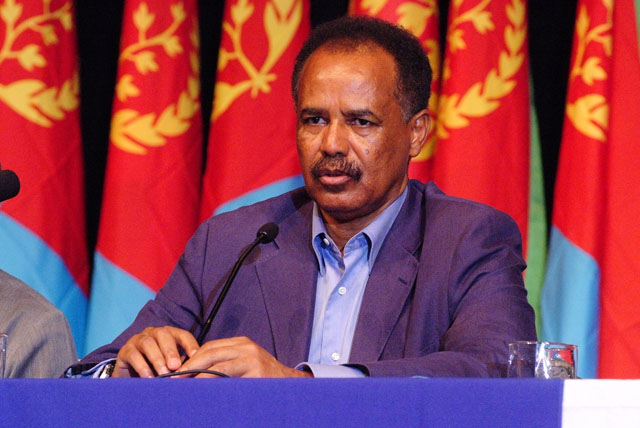

Isaias Afwerki

Eritrea denies the claims, but has refused entry to a UN rapporteur on human rights, appointed two years ago to investigate the reasons for the growing exodus. The rapporteur, Sheila Keetharuth, is due to publish a full report in June, but her interim findings are already grim enough, speaking of “indefinite national service; arbitrary arrests and detention, extrajudicial killings, torture, and inhumane prison conditions.”

The main reason for people fleeing, however, is Eritrea’s draconian military service program. Officially, it exists in the event of a resumption of the war again with Ethiopia, which did flare up again between 1998 and 2000 with the loss of 70,000 lives. But as in North Korea, it has become an excuse to keep the country’s menfolk in conditions of near-indefinite vassalage. Recruits speak of being forced to work in gold mines, with military service lasting up to ten years or more, and harsh penalties for deserters.

Such is the exodus from Eritrea that even the Afwerki government now seems to be softening its line, apparently anxious about the “brain drain” effect of losing so many of its young people. Following the visit of a British government delegation that visited to the country last December, current Home Office thinking is that Eritreans who flee the country illegally – including deserters – are no longer automatically treated as “traitors”if they return. That, though, has not stopped the current flow of people, and with ever larger foreign diasporas – an estimated 40,000 now live in London alone – the “pull” factor of Europe is likely to remain.

ESTONIA – Estonia recruits volunteer army of ‘cyber warriors’

Estonia has recruited a “ponytail army” of volunteer computer experts who stand ready to defend the nation against cyber attack.

The country’s reserve force, the Estonian Defense League, has a Cyber Unit consisting of hundreds of civilian volunteers, including teachers, lawyers and economists.

Lt Johannes Kert at the K5 barracks, the home of the NATO Cyber Defence Centre, Tallinn, Estonia (Photo: Geoff Pugh/The Telegraph)

The Baltic nation of 1.3 million people is one of the most technologically advanced in the world: almost every banking transaction takes place online and 30 per cent of all votes in the last general election were cast electronically.

But this also makes Estonia acutely vulnerable. In 2007, the country suffered one of the biggest cyber attacks in history when the websites of banks, government ministries and the national parliament were swamped with data.

Responsibility for this assault was never established, but the finger of suspicion pointed towards neighbouring Russia. The trigger for the event was a controversial decision to relocate a Soviet war memorial in the Estonian capital, Tallinn.

If an emergency of this kind were to recur, Estonia’s cyber defenders would be mobilised. “We call them guys with ponytails – but we don’t all have ponytails,” said Tanel Tetlov, a 33-year-old volunteer member of the Cyber Unit.

“The worst part of being a defender is you never know where the attacker is going to hit you,” added Mr Tetlov. “He can choose a clear strike, but you have to defend every door and window.”

The methods of cyber warfare are constantly changing. One common form of attack is a “distributed denial of service”– known as a “D-DOS” – whereby a server is jammed with cascades of data. This can paralyze vital websites, including those handling financial transactions.

Most of the cyber assaults on Estonia in 2007 fell into this category. Today, “D-DOS” incidents are regarded as one of the less sophisticated forms of attack. Criminal gangs or even individuals are capable of launching them.

As a volunteer, Mr Tetlov has helped to fend off dozens of “D-DOS” events. The danger is that a hostile state could employ them as a diversionary tactic. “You could use it as a pawn, as the first move in the game,” said Mr Tetlov. “It could be a diversion to turn your attention elsewhere while they are doing something more damaging.”

Thwarting a cyber attack of this kind starts with identifying where the flood of data is coming from. Once that has been established, the relevant network can be isolated.

This takes expertise and manpower. Governments often find it difficult to employ people with the required skills because they [can get] high salaries in the private sector. Estonia’s solution is to have a pool of civilian volunteers available in an emergency. …

Estonia’s Cyber Unit has a permanent staff of just three people, based in a building in Tallinn once used by Soviet Signals Intelligence. In his office, Andrus Padar, the commander of the unit, organizes volunteers and monitors the continuous round of cyber attacks across the world.

One website tracks these events in real time, identifying – so far as possible – the origins and targets of the assaults. The same countries tend to appear: America, Russia, China and Saudi Arabia.

Cyber warfare gives hostile states the ability to damage their foes covertly and deniably. A full scale offensive might destroy power systems, paralyse financial transactions and freeze essential services – all without the culprit being known.

“What will happen for the next three weeks if you cannot use your credit card or your bank card?” asked Mr Padar. “You can’t buy food or gas – then life will stop.”

The exact number of volunteers who would try to save Estonia from this fate is classified, but Mr Padar said that about 1 per cent of all the country’s information technology experts had joined the Cyber Unit.

He added: “Cyber war is a little bit close to a nuclear war: you are talking about critical services being removed.”

(The news briefs above are from wire reports and staff reports posted at The Washington Post & Daily Mail on April 25/26, London’s Daily Telegraph on April 25 and April 26.)

Background

NEPAL - Religion:

Nepal is famous as the world's only Hindu Kingdom.

- The overwhelming majority of the Nepalese population follows Hinduism. Shiva is regarded as the guardian deity of the country. Shiva is one of the main deities of Hinduism. He is the supreme god within Shaivism, one of the three most influential denominations in contemporary Hinduism.

- Nepal is home to the famous Lord Shiva temple, the Pashupatinath Temple, where Hindus from all over the world come for pilgrimage.

- Lumbini is a Buddhist pilgrimage site and UNESCO World Heritage Site site in the Kapilavastu district. Traditionally it is held to be the birthplace in about 563 B.C. of Siddhartha Gautama,…who, as the Buddha Gautama, gave birth to the Buddhist tradition.

- The Buddhist holy site of Lumbini is bordered by a large monastic zone, in which only monasteries can be built. All three main branches of Buddhism exist in Nepal.

- Buddhism is also the dominant religion of the thinly populated northern areas, which are mostly inhabited by Tibetan-related peoples, such as the Sherpa.

- The Buddha, born as a Hindu….

- Differences between Hindus and Buddhists have been minimal in Nepal due to the cultural and historical intermingling of Hindu and Buddhist beliefs. Moreover traditionally Buddhism and Hinduism were never two distinct religions in the western sense of the word. In Nepal, the faiths share common temples and worship common deities.

- Most of the festivals in Nepal are Hindu.

- Islam is a minority religion in Nepal, with 4.2% of the population being Muslim according to a 2006 Nepalese census. Mundhum, Christianity and Jainism are other minority faiths. (from wikipedia)

ERITRIA

It was to flee this modern-day Sparta that Henok Tekle, 28, took his chances on a people smuggling boat across the Mediterranean back in 2002.

“I was conscripted into the army as a 16-year-old,” Mr. Tekle, who now lives in London, told The Sunday Telegraph last week. “Life in the military was very tough - there was often hardly food or health care, but they didn’t care. And a lot of the time we weren’t learning about fighting, but just doing building work to make houses for people of high rank in the military. After about two months, I decided I was going to escape.”

Having slipped across the border to Sudan, Mr Tekle and some friends headed for Libya, a gruelling three-week truck journey across the Sahara. Many who attempt it die of thirst or starvation, and the sand dunes that Mr Tekle drove through were littered with skeletons.

“Our driver told us: ’they were trying to go Libya like you, but they died on the way,” said Mr Tekle. “It wasn’t just one or two, I saw many skeletons.”

Once in Libya, Mr. Tekle and his friends paid $1,000 for passage on a people-smuggler across the Mediterranean. On the second day of the journey, a storm whipped up, and soon the boat was in pieces.

“I don’t know him to swim, and I thought that was it, I am going to die here,” said Mr. Tekle. “I didn’t even want to talk to my friends, I was in shock.”

The Maltese navy eventually rescued the ship, only for another shock to greet Mr. Tekle after he lodged an asylum bid in Malta. The Eritrean government had learned he and his friends were there, and pressured the Maltese to send them back, saying that as the war was over, they had nothing to fear.

“Somehow the Maltese believed them, and we ended up being handcuffed and flown back there. They took us into a warehouse full of soldiers all carrying Kalashnikovs. I was terrified.”

His fears were justified. He says he spent the next 18 months in prison, being beaten on a daily basis. Two of his friends were killed, and others went mad due to the heat and disease. “I got malaria and all they would give you was paracetomol,” he said. “It was a way of killing us over a long time - if you spent three or four years there you were finished.”

Eventually Mr. Tekle escaped again, taking advantage of a party held by his captors to Eritrea’s independence day. This time he went straight to a UN refugee centre in Sudan, and was resettled in Britain in 2005 under an asylum program. Since then he has made strenuous efforts to integrate, learning fluent English, holding down a job in construction, and watching the news each night to learn more about his adopted homeland.

“If you ask me where hell is on earth, I would probably say two places: Eritrea and North Korea,” added Mr Tekle. “There is no food, no electricity, and your friends can be killed in front of you. No wonder everyone is leaving - there is no hope.” (from the Telegraph article above)