The Department of the Internet

Weekly Editorial — Posted on November 13, 2014

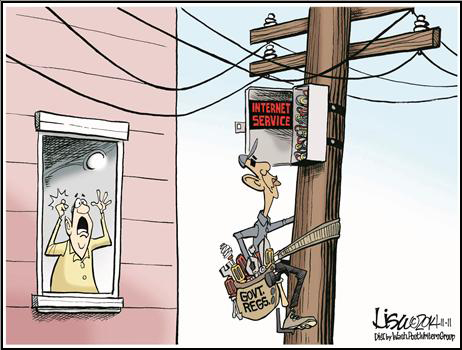

For years the FCC has been inching toward imposing net-neutrality rules, which are sold as a way to ban Internet service providers from discriminating against content providers. In reality such rules would dictate what ISPs (Internet Service Providers) like Comcast and Verizon can charge for their services. The Silicon Valley crowd particularly likes the net-neut idea, because it would mean cheaper access for companies like Google and Netflix, who are heavy bandwidth users. President Obama’s announcement is likely to delight them-and liberal groups supporting supposed Internet “fairness” – because now FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler will be under enormous pressure to do the White House’s bidding.

But the Internet cannot function as a public utility. First, public utilities don’t serve the public; they serve themselves, usually by maneuvering through Byzantine* regulations that they helped craft. [*Byzantine: excessively complicated, typically involving a great deal of administrative detail]. Utilities are about tariffs, rate bases, price caps and other chokeholds that kill real price discovery and almost guarantee the misallocation of resources. I would know; I used to work for AT&T in the early 1980s when it was a phone utility. Its past may offer a glimpse of the broadband future. Innovation gets strangled.

- Bell Laboratories – owned by AT&T – invented the transistor in 1947, the basic building block of today’s telecommunications and computing. But AT&T was one of the last businesses to use the innovation. Why? Because the company had a 10-year supply of the old technology – vacuum tubes – and waited until they ran out before converting to using AT&T’s own invention.

- It was much the same with touch-tone dialing, which was invented in 1941 but not rolled out until the 1970s. Though touch-tone was easier to use than rotary-dial phones, and cheaper, AT&T charged $10 a month extra for the service – because the company could. Bell Labs funded a study to decide the size, color and coding of the touch-tone buttons. The study’s director received a report with hundreds of ideas but didn’t like any of them. Instead, he insisted on gray buttons, and just 12 of them.

- More utility follies? The first cellphone call was made in St. Louis in 1946 with AT&T’s Mobile Telephone Service, but the company let the innovation wither. It took until 1983 for Motorola to introduce the now comically unwieldy DynaTAC, a cellphone that weighed more than 2 pounds – but that private-sector effort is what ultimately led to today’s 4-ounce iPhone.

- Oh, and data. I worked in a group at Bell Labs that developed the early 300 and 1200 bit-per-second modems. We wanted to test them by sending data from our Western Electric factory in Illinois to our site in New Jersey. But no luck, because Illinois Bell hadn’t set tariffs for data. We had the technology, but regulators lagged far behind. …

- If the Internet is reclassified as a utility, online innovation will slow to the same glacial pace that beset AT&T and other utilities, with all the same bad incentives. Research will focus on ways to bill you – as wireless companies do with calling and data plans – rather than new services. Imagine if Uber had to petition the FCC to ask for your location.

The president’s statement Monday was not the first time he has promoted net neutrality, just the most emphatic. At an Oct. 9 town-hall meeting in Los Angeles, he said: “I made a commitment very early on that I am unequivocally committed to net neutrality. I think . . . it’s what has unleashed the power of the Internet, and we don’t want to lose that or clog up the pipes.” Then he, however awkwardly, implored the FCC to act: “My appointee, Tom Wheeler, knows my position. Now that he’s there, I can’t just call him up and tell him exactly what to do. But what I’ve been clear about, what the White House has been clear about, is that we expect whatever final rules to emerge to make sure that we’re not creating two or three or four tiers of Internet.”

Maybe Mr. Wheeler didn’t get the message last month and the White House thought he needed some public hectoring. Or maybe he has been only sidling up to the idea because he knows deep down that network neutrality is a fuzzy concept that can’t possibly exist in nature. Comcast might want to charge Netflix customers $5 a month for a fast lane, but if Google Fiber is in town and offers Netflix with no extra charges, that’s what customers will choose.

The beauty of competition is that you get network neutrality for free. AT&T cut long-distance rates in the 1980s when MCI and Sprint started competing fiercely. Calling from San Francisco to New York became cheaper than calling from San Francisco to San Jose, because California tariff prices were still highly regulated. The same thing happened to international rates once Skype offered voice and video connections free online. And it is no surprise that AT&T hurried to offer its own gigabit Internet connection in Austin, Texas, as soon as Google Fiber showed up. Now everyone in Austin has access to a fast lane.

And the rest of us? “At 25 Mbps, there is simply no competitive choice for most Americans,” Mr. Wheeler said in a September speech. Treating the Internet like a utility would ensure things stay that way.

The president might think he’s doing a favor for Americans, but utilities are utopias only on paper. With no competition to stimulate investment, capabilities will wither. Eventually a federal bureaucracy will be needed to help allocate the scarce broadband resources. In that vaguely neutral world, everybody gets access to the same resources. Well, except for the government – it of course will need special, superfast access. You want cheap, ubiquitous and naturally neutral broadband? Promote competition and outlaw utilities.

Mr. Kessler, a former hedge-fund manager, is the author, most recently, of “Eat People” (Portfolio, 2011).

Published Nov. 10, 2014 at The Wall Street Journal. Reprinted here Nov. 13, 2014 for educational purposes only. Visit the website at wsj .com.

Questions

1. What is the main idea of Mr. Kessler's commentary?

2. Mr. Kessler concludes by asserting: "The president might think he’s doing a favor for Americans, but utilities are utopias only on paper. With no competition to stimulate investment, capabilities will wither. Eventually a federal bureaucracy will be needed to help allocate the scarce broadband resources. In that vaguely neutral world, everybody gets access to the same resources. Well, except for the government - it of course will need special, superfast access. You want cheap, ubiquitous and naturally neutral broadband? Promote competition and outlaw utilities."

Are you surprised by this assertion? Explain your answer.

3. Do you argree or disagree with Mr. Kessler's opposition to President Obama's call for "net neutrality"? Explain your answer.