redo Jump to...

print Print...

(by Paul H. Tice, The Wall Street Journal) – Here is a college quiz. While many parts of the U.S. economy struggle to recover from the Great Recession of 2008-09, one domestic industry is experiencing a technology-driven expansion in which American innovations have led to countless new company startups, a surge in hiring and some of the highest-paying entry-level jobs for graduating college seniors.

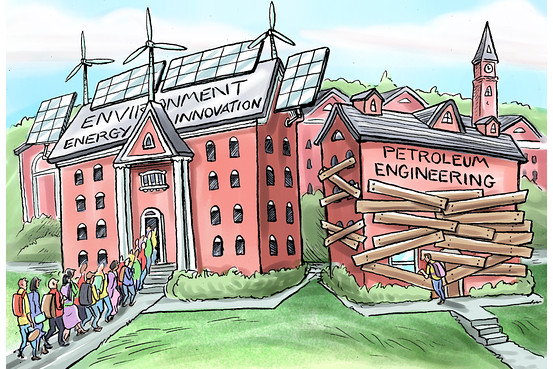

How are the nation’s universities responding so students might prepare for a promising career in this growing and intellectually challenging field? By largely ignoring it. Why? Because the industry is oil and gas.

(Chad Crowe)

This fact may surprise the casual campus observer, since almost every U.S. college these days seems to have an energy research institute. Most of these energy think-tanks, however, are run by academic advocates of theories about global warming and man-made climate change, most of whom view energy through green-colored lenses. The research focus is more on promoting the clean, sustainable, renewable, non-CO2-emitting energy of the future, as opposed to studying and analyzing the hydrocarbon resources of the here and now.

For some of these programs, the agenda is obvious and stated in bold print over the door. Names such as the Yale Climate & Energy Institute and the Princeton Center for Energy and the Environment make clear that the study of energy needs to be chaperoned and monitored. The labeling is less obvious for others, but the result is the same. Visit the websites of the neutrally named Cornell Energy Institute, MIT Energy Initiative and Penn Center for Energy Innovation, and you would think you were looking at AlGore .com.

My alma mater, Columbia University, recently launched its own Center on Global Energy Policy, with the mission to “improve the quality of energy policy and energy dialogue through objective, balanced and understandable analysis.” The center is headed by Jason Bordoff, former senior director for energy and climate change on the staff of the National Security Council in the Obama administration, who is on record calling for carbon caps and immediate government action to drive down greenhouse-gas emissions. So much for balance.

With all of these research institutes, the messaging is consistent: Fossil-fuel energy is a problem to be solved, a challenge to be overcome, a sector that needs to be transformed and the relic of an industrial state from which to evolve. The policy prescriptions issued by these think-tanks are often presented as moral imperatives, which helps to cut down on the debate.

More troubling is how this ideological bias filters into the college curriculum, both through the content of introductory natural science courses required of all students and the choice of majors and specialty electives offered by technical undergraduate schools.

Based on survey data compiled by the National Association of Colleges and Employers, the top-paying undergraduate major in 2013 was petroleum engineering, with an average starting salary of $97,000. How many of the country’s top engineering schools offer such a major? Outside of Texas, Colorado and Oklahoma, not many. Often the closest approximation is a bachelor of science degree in Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences or the equivalent, with a handful of classes on petrology and geophysics safely outnumbered by myriad courses on environmental science, climatology, global-warming theory and alternate-energy sources.

The oil and gas industry has been historically volatile and marked by boom-and-bust cycles caused by fluctuating commodity prices, with company prospects often tied to hit-or-miss exploratory drilling. Not surprisingly, the industry has struggled with periodic brain drain since the 1980s as students looking for steady employment and career growth have been turned off by such uncertainty.

Technological advances such as seismic imaging, horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing—all developed by private companies—have removed much of this volatility and changed the nature of the industry to more of a manufacturing operation. But now another source of even greater uncertainty has been injected into the mix: political and regulatory risk. This is one energy lesson that undergraduates are hearing loud and clear from their professors.

How many college students have been discouraged from considering a field in petroleum engineering or traditional energy finance because of the rational concern that the current Environmental Protection Agency-led attack on coal will move next to target oil and gas? Conversely, how many recent undergraduates have been led down the green garden path toward a career in renewable energy, only to receive a hard-knock, real-life economics lesson in the commercial failures of solar, wind, ethanol, battery and fuel-cell technologies?

Obviously, having proponents of man-made-climate-change theory running energy-research institutes at the college level is an example of inmates taking over the asylum, but there is method to this madness. Over the past 25 years, the environmental movement has been very successful using a two-pronged approach to push its anti-fossil-fuel agenda.

The first prong involves leveraging the U.S. courts and executive agencies to directly control the oil and gas industry through government regulation and taxation. The second involves indirect control through thought leadership and opinion-shaping. Culturally and generationally, man-made climate change is becoming accepted wisdom due to the steady indoctrination taking place in our universities.

Mr. Tice works in investment management and is a former Wall Street energy-research analyst.

Published April 7, 2014 at The Wall Street Journal. Reprinted here April 10, 2014 for educational purposes only. Visit the website at wsj.com.

Questions

1. What is the main idea of Paul Tice’s commentary?

2. In paragraph 8, Mr. Tice writes: “Based on survey data compiled by the National Association of Colleges and Employers, the top-paying undergraduate major in 2013 was petroleum engineering, with an average starting salary of $97,000. How many of the country’s top engineering schools offer such a major? Outside of Texas, Colorado and Oklahoma, not many.”

Do you think colleges are doing a disservice to their students by not offering a major in petroleum engineering because it is not “green” energy? Explain your answer.

3. Re-read the last 3 paragraphs of the article. Mr. Tice concludes by saying, “Culturally and generationally, man-made climate change is becoming accepted wisdom due to the steady indoctrination taking place in our universities.” What is your reaction to this assertion? (agreement, anger, puzzlement, concern…) Explain your answer.