God Bless the Doolittle Raiders

Weekly Editorial — Posted on April 23, 2015

(by Larry Thornberry, The American Spectator) – It may have been the most unexpected, certainly one of the most heroic wake-up calls in history. It should be remembered and honored more than it is.

The spring of 1942 was not a happy time for civilization. Hitler and his Nazis owned or controlled most of Europe. After committing mass murder and mayhem at Pearl Harbor in December of 1941, the Imperial Japanese Navy was rampaging unchecked in the Pacific, pitching a shutout against the underequipped and undermanned Brits and Americans. Almost as much of America’s Pacific fleet lay at the bottom of Pearl Harbor than was available to engage the Japanese.

The game-changing sea battles at Coral Sea and Midway would tilt the Pacific equation more in the Allies’ favor in May and June. But in April, Americans were starved for good news. Starved for any indication that we could strike back at our enemies. Enter 80 American heroes, volunteers, who managed to do what no civilian and almost no one in uniform thought was possible in April of 1942, to bomb the mainland of Japan.

So much of the raid, led by then Lieutenant Colonel Jimmy Doolittle, was somewhere between improbable and fantastic. The whole daring project was based on the near delirium that a 16-ship American Navy task force, based around the carrier USS Hornet, could approach the mainland of Japan undetected and then launch 16 medium bombers from its flight decks (medium bombers!), bombers that would dump their deadly loads on Tokyo and then fly on to unoccupied China.

As a veteran of carrier battle-group operations in the Mediterranean and North Atlantic, when I watch the film of those B-25s lumbering down the Hornet’s flight deck and struggling into the air, I still can’t believe they stay aloft. They seem to stay airborne out of sheer determination, and against all laws of physics.

The original idea for the raid came from Navy Captain Francis Low, who had seen B-25s at a Norfolk naval airfield that had been painted to represent a carrier deck. Fortunately for the country, Low was not institutionalized, and his idea was taken seriously. Volunteer Army Air Forces crews went through extensive and very secret training on short takeoffs, most of it at Eglin Air Field in North Florida, with the help of Navy aviators. The planes that were used on the raid carried extra fuel tanks to accommodate their long trip, but were stripped of everything unnecessary, including most guns, that would add weight to the planes and therefore increase fuel consumption.

Those who’ve seen the documentaries, or the fine movie about the raid, 30 Seconds Over Tokyo, starring Spencer Tracy as Colonel Doolittle, know that the task force was spotted by a Japanese picket boat 10 hours before and 200 miles further from Tokyo than the planned launch. This was bad news for the raiders, and for the picket boat, which was sent to the bottom by gunfire from an American cruiser. But the word of the task force’s presence had gone out.

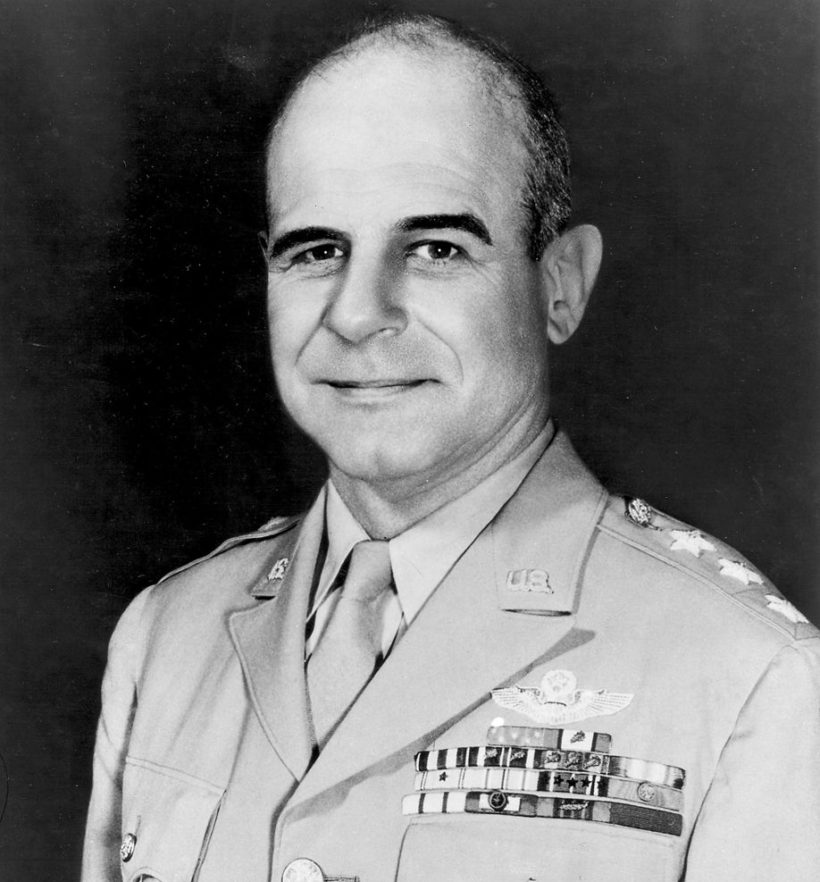

Lt. General James Doolittle

Doolittle’s B-25s were launched early and flew in single-file toward Japan at just-above-wave-top-level to avoid detection. Six hours later, about noon Tokyo time, they began appearing over their targets and dropped their payloads of four 500-pound bombs (three high explosive and one incendiary). The damage the raiders caused on the ground was real enough but not extensive. The psychological and strategic damage was more important. The Japanese now knew they were not out of reach at home of the war they had started, and they recalled a significant number of troops to Japan for home defense purposes. In America, and among the other allies, the news was most welcome. American morale soared.

After their bomb runs, the raiders enjoyed mixed fates. Some crews bailed out over China, others crash-landed. Only three of the raiders were killed in action that day, all in landing attempts, and eight became prisoners of the Japanese. Three of these were executed by the Japanese. Another died of disease while a POW. The other 69 eventually made their way home.

This significant and inspiring chapter in American history took place 73 years ago last Saturday. Those looking to read or see news of this momentous event were not much rewarded over the weekend. For too many, World War II is ancient history. Those who fought it in our name forgotten. And that’s a shame. If America ever stops producing selfless heroes like the Doolittle raiders, we will cease to be America. They should be remembered and honored.

Only two of Doolittle’s raiders remain alive today, retired Lieutenant Colonel Dick Cole, 99, and former Staff Sergeant David Thatcher, 93. Doolittle himself retired from the Air Force in 1985 at the rank of general. He died in 1993 in Pebble Beach, California at the age of 96. God bless the surviving raiders, their brave colleagues who have gone on, and the country that can produce men like these.

Published April 20, 2015 at Spectator .org. Reprinted here on April 23 for educational purposes only. May not be reproduced on other websites without permission from The American Spectator.

Questions

1. Tone is the attitude a writer takes towards his subject: the tone can be serious, humorous, sarcastic, ironic, inspiring, solemn, objective, cynical, optimistic, encouraging, critical, enthusiastic… Which word do you think best describes the tone of Mr. Thornberry’s commentary? Explain your answer.

2. The purpose of an editorial/commentary is to explain, persuade, warn, criticize, entertain, praise or answer. What do you think is the purpose of this editorial? Explain your answer.