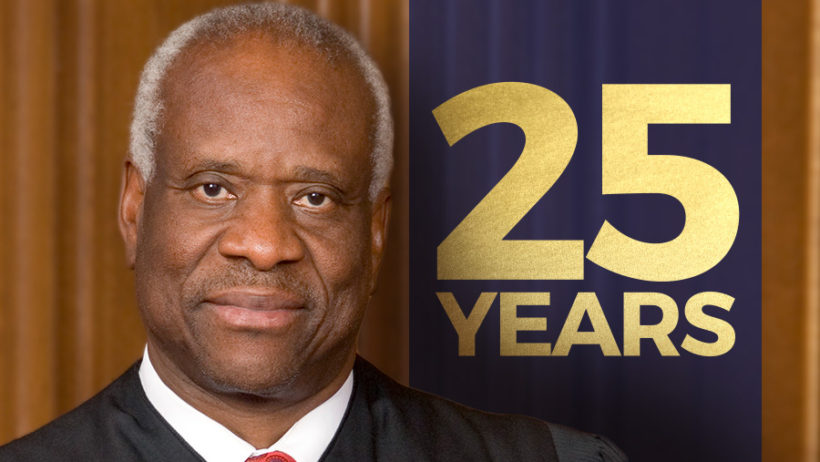

Even left-leaning scholars agree that Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas has become one of the most esteemed justices on the high court. (Image: Wikimedia Commons and Shannon Henderson / The Stream)

redo Jump to...

print Print...

(by Mark Paoletta, The Washington Post) – Sunday was the 25th anniversary of Clarence Thomas being sworn in as a justice of the Supreme Court. From his beginnings in Georgia, where he lived in a shanty, he has become the longest-serving black justice on the nation’s highest court. He emerged dignified from an undignified Senate confirmation and went on to produce a body of jurisprudence that has been praised by constitutional scholars across the ideological spectrum.

But because he’s a black man who challenges liberal orthodoxy, his legacy has often been minimized.

His is a story that should be celebrated by all Americans. [The fact] that it isn’t [celebrated] is a travesty.

As Supreme Court correspondent Jan Crawford wrote, “From the beginning, Justice Thomas was an independent voice” who began making his mark as soon as he arrived at the court. Since then, he has repeatedly led the court back to the original meaning of the Constitution with thought-provoking separate writings that explore the historical record.

The liberal-leaning SCOTUSBlog’s Tom Goldstein, a well-regarded Supreme Court practitioner, says, “I disagree profoundly with Justice Thomas’s views on many questions,” but if “the measure of a Justice’s greatness is his contribution of new and thoughtful perspectives that enlarge the debate, then Justice Thomas is now our greatest Justice.”

Why, then, is he rarely mentioned along with great jurists like Oliver Wendell Holmes, Felix Frankfurter or Antonin Scalia, his recently departed contemporary?

One reason is lingering sentiment about Thomas’ confirmation process, which indeed was, as he described it, an unjust and malicious “high-tech lynching.” Perhaps another is Thomas’ silence on the bench. He prefers to listen, and not ask questions.

But if the measure of judicial accomplishment is the number and quality of opinions a justice writes — and not the questions he rattles off during oral arguments — then Thomas is among the most impressive justices: He has now written more than 500 opinions, many of them contributing new and painstakingly researched analysis.

His opinions in United States v. Lopez, McIntyre v. Ohio Elections Commission and McDonald v. City of Chicago are just some examples from the illustrious list.

Mainly, though, it’s that Thomas never wavered from a set of principles many liberals don’t think a black man can legitimately hold. He believes in individual rights, not group rights, a view enshrined in the Declaration of Independence. He opposes racial preferences both because they are bad policy and because they have no basis in the Constitution.

In his concurrence in Fisher v. University of Texas at Austin, which involved a challenge to affirmative action, Thomas quoted arguments in the landmark Brown v. Board of Education that “No State has any authority under the equal-protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to use race as a factor in affording educational opportunities” and continued that the “Constitution does not pander to faddish theories about whether race mixing is in the public interest.

“All applicants must be treated equally under the law, and no benefit in the eye of the beholder can justify racial discrimination.”

As a result, Thomas has earned the scorn and disdain of traditional black civil-rights leadership and special-interest groups — his opinions are a threat to their calls for quotas and set-asides.

Critics have not only dismissed his record, they have attempted to minimize him, personally. More than one has characterized him as an unqualified appointment, despite his having graduated from Yale Law School, chaired a federal agency and served as a federal circuit judge.

Some take the criticism further, claiming he was the beneficiary of affirmative action programs — an assertion he rejects — and, by opposing such programs, he has essentially turned his back on the black community.

Nothing could be further from the truth. As University of California at Berkeley law professor Angela Onwuachi-Willig, a self-described “liberal black womanist,” concludes, Thomas’ opinions reflect a profound concern for the black community. And, she writes, he “has been unfairly subject to the stereotype of black incompetence.”

Thomas came to resent the stigmatizing impact of racial preferences, and critics who suggest he is not qualified and on the court only because of his race make his case for him.

For those of us who worked on his confirmation and went through that terrible ordeal with him, his stellar record has only confirmed the value of that fight.

History will look kindly upon Thomas’ judicial legacy and on him as an individual. The people who know him best certainly do, and in time, I believe, most Americans will, too.

— Mark Paoletta served as assistant counsel to President George H.W. Bush and worked on Justice Clarence Thomas’s confirmation to the Supreme Court. He practices law in Washington, D.C.

Special to The Washington Post. Published October 21, 2016 at The Washington Post. Reprinted here on October 27 for educational purposes only.

Questions

1. What is significant about Clarence Thomas’ tenure on the U.S. Supreme Court?

2. How do SCOTUSBlog’s Tom Goldstein and UCLA law professor Angela Onwuachi-Willig view Justice Thomas’ opinions on the court?

3. Consider the following:

- Thurgood Marshall, who served from 1967-1991, was the first African American appointed to the U.S. Supreme Court.

- Since then, Clarence Thomas is the only other African-American justice. He was appointed as Marshall’s successor in 1991.

- The Smithsonian’s new National Museum of African American History and Culture recently opened in Washington DC.

- With more than 36,000 artifacts, the museum is “devoted exclusively to the documentation of African-American life, history and culture.”

- But the story of Justice Thomas — who rose from bitter poverty in the Jim Crow South to a seat on the nation’s highest court, is ignored.

- Our nation’s second black Supreme Court justice is not included in the museum. Its official excuse: “[We] can’t tell every story in our inaugural exhibitions.”

Mr. Paoletta asserts in this commentary, “[Justice Thomas’] is a story that should be celebrated by all Americans. That it isn’t is a travesty.”

a) Do you agree with this assertion? Explain your answer.

b) Ask a parent or grandparent the same question.

Background

We recommend Justice Thomas’ memoir, My Grandfather’s Son. Read the Amazon description of the book below:

Thomas was born in rural Georgia on June 23, 1948, into a life marked by poverty. His parents divorced when Thomas was still a baby, and his father moved north to Philadelphia, leaving his young mother to raise him and his brother and sister on the ten dollars a week she earned as a maid. At age seven, Thomas and his six-year-old brother were sent to live with his mother’s father, Myers Anderson, and her stepmother in their Savannah home. It was a move that would forever change Thomas’s life.

His grandfather, whom he called “Daddy,” was a black man with a strict work ethic, trying to raise a family in the years of Jim Crow. Thomas witnessed his grandparents’ steadfastness despite injustices, their hopefulness despite bigotry, and their deep love for their country. His own quiet ambition would propel him to Holy Cross and Yale Law School, and eventually — despite a bitter, highly contested public confirmation — to the highest court in the land. In this candid and deeply moving memoir, a quintessential American tale of hardship and grit, Clarence Thomas recounts his astonishing journey for the first time, and pays homage to the man who made it possible.

The following points are from an October 19 New York Post Editorial, “Turning Clarence Thomas into an invisible man”:

- With more than 36,000 artifacts, the museum in Washington, DC, is “devoted exclusively to the documentation of African-American life, history and culture.” But Thomas — who rose from bitter poverty in the Jim Crow South to a seat on the nation’s highest court — isn’t notable enough.

- Worse, he does pop up in a different exhibit: one devoted to Anita Hill, whose only claim to fame is that she accused Thomas of sexual harassment during his confirmation hearings in 1991.

- The excuse for honoring Hill is that she was fighting against an “all-white, all-male Senate committee.” No, she wasn’t: Most of the committee was on her side, because Democrats desperate to derail Thomas’ confirmation ran it.

- For decades now, Clarence Thomas has been pilloried for refusing to play the role that (mostly white) liberals would assign him. It’s a betrayal of the museum’s mission to honor Hill, even as it makes Thomas into an invisible man.

- Ignored in the Smithsonian’s new National Museum of African American History and Culture is the nation’s second black Supreme Court justice, and here’s its official excuse: They can’t “tell every story in our inaugural exhibitions.”