Supreme Court upholds Michigan’s ban on racial preferences in university admissions

Daily News Article — Posted on April 24, 2014

(by Robert Barnes and William Branigin, The Washington Post) – The Supreme Court on Tuesday ruled by a 6-2 vote that Michigan voters had a right to ban affirmative action in their state via a ballot initiative which amended the state’s constitution.

(by Robert Barnes and William Branigin, The Washington Post) – The Supreme Court on Tuesday ruled by a 6-2 vote that Michigan voters had a right to ban affirmative action in their state via a ballot initiative which amended the state’s constitution.

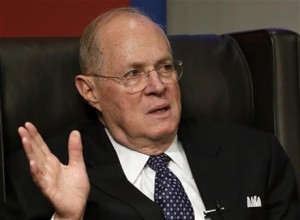

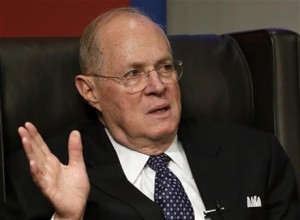

In the controlling opinion, Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy stressed that the case was “not about the constitutionality, or the merits, of race-conscious admissions policies in higher education.” Instead, the case was about “whether, and in what manner, voters in the States may choose to prohibit the consideration of racial preferences in governmental decisions, in particular with respect to school admissions.”

The case, referred to Schuette v. Coalition to Defend Affirmative Action, reviewed a 2006 Michigan ballot initiative that amended the state Constitution to ban the consideration of race or sex in public education, government contracting and public employment. (California, Florida and the state of Washington have similar prohibitions.)

In 2012, the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals said the Michigan initiative violated the U.S. Constitution’s equal protection clause [in the 14th Amendment]. Because it came in the form of a constitutional amendment, the appeals court said the new rule “reordered the political process” in a way that put special burdens on racial minorities.

“Rather than undoing an act of popularly elected officials by simply repealing the policies they created, Michigan voters repealed the admissions policies that university officials created and took the additional step of permanently removing the officials’ power to reinstate them,” the appeals court wrote. “Had those favoring elimination of all race-conscious admissions policies successfully lobbied the universities’ admissions units, just as racial minorities did to have these policies adopted in the first place, there would be no equal protection concern.”

Oct. 13, 2013 AP file photo showing Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy speaking at the University of Pennsylvania law school in Philadelphia. The Supreme Court on Tuesday upheld Michigan’s ban on using race as a factor in college admissions. The justices said in a 6-2 ruling that Michigan voters had the right to change their state constitution to prohibit public colleges and universities from taking account of race in admissions decisions. The justices said that a lower federal court was wrong to set aside the change as discriminatory. Kennedy said voters chose to eliminate racial preferences because they deemed them unwise. (AP Photo/Matt Slocum)

However, Kennedy argued that the court of appeals’ logic was “inconsistent with the underlying premises of a responsible, functioning democracy.” He wrote, “One of those premises is that a democracy has the capacity–and the duty–to learn from its past mistakes; to discover and confront persisting biases; and by respectful, rationale deliberation to rise above those flaws and injustices. It is demeaning to the democratic process to presume that the voters are not capable of deciding an issue of this sensitivity on decent and rational grounds.”

Kennedy was joined by Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Samuel Alito. Justices Antonin Scalia and Clarence Thomas agreed with the outcome, but would have gone further to prohibit racial preferences. Justice Stephen Breyer also agreed with the judgment, abandoning the liberal wing of the court.

Justice Sonia Sotomayor dissented, joined by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Justice Elena Kagan did not take part in the decision. [Justice Kagan recused* herself from the case because she was the Obama administration’s U.S. solicitor general when the case was before the lower courts. *Recuse means to remove (oneself) from participation to avoid a conflict of interest]

Sotomayor, for the first time in her tenure on the court, noted how strongly she disagreed with the decision by reading her dissent from the bench.

Sotomayor wrote in her 58-page dissenting opinion. “For members of historically marginalized groups, which rely on the federal courts to protect their constitutional rights, the decision can hardly bolster hope for a vision of democracy that preserves for all the right to participate meaningfully and equally in self-government.”

An appeals court had said that a Michigan constitutional amendment banning the use of racial preferences in university admissions, approved by 58 percent of the state’s voters in 2006, had restructured the political process in a way that unfairly targeted minorities.

The decision to overturn the ruling was not surprising. At oral arguments, a majority of the justices had been skeptical of the appeals court’s rationale and questioned how requiring the admission process to be color-blind could violate the constitution’s guarantee of equal protection.

Kennedy said the court’s decisions that allow race to be used in limited ways in admission decisions did not dictate that it must be used.

In a sense, the decision does not change what states are allowed to do, and even many conservative states–Texas, for instance–have been adamant that they be allowed to consider race in order to achieve diverse student bodies.

But the court’s decision could encourage opponents of affirmative action to press for action, using the decision as an impetus. California, Florida and the state of Washington already have similar prohibitions on the use of affirmative action in college admissions etc.

At issue at the Supreme Court was language [from Michigan’s constitutional amendment] that says state colleges and universities “shall not discriminate against, or grant preferential treatment to, any individual or group on the basis of race, sex, color, ethnicity, or national origin.”

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 6th Circuit, which narrowly tossed out the Michigan amendment, ruled that there was a difference between not using affirmative action and banning it in the state constitution. The latter violates the principle that minorities must be allowed to fully participate in creating laws and that “the majority may not manipulate the channels of change so as to place unique burdens on issues of importance to them,” Judge R. Guy Cole Jr. wrote.

His comparison was that while residents of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula may lobby decision-makers to grant preferences to their underrepresented students, minority groups would now have to change the constitution before even having a chance to advocate racial considerations because of the amendment.

Compiled from news reports at CBS News and The Washington Post. Reprinted here for educational purposes only. May not be reproduced on other websites without permission from CBS News and The Washington Post.

Background

Michigan Civil Rights Initiative

- In 2006, Michigan voters passed the Michigan Civil Rights Initiative (MCRI) by a margin of 58 to 42 percent. This initiative made it unconstitutional for the state to "discriminate against, or grant preferential treatment to, any group or individual on the basis of race, sex, color, ethnicity or national origin."

- On Tuesday, April 22, 204, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld Michigan's voter-approved ban on race-based university admissions.

- Seven other states have passed similar measures.

Affirmative action explained:

- Affirmative action refers to policies that take factors including “race, color, religion, sex, or national origin” into consideration in order to benefit an underrepresented group “in areas of employment, education, and business”. The concept of affirmative action was introduced in the early 1960s as a way to combat racial discrimination in the hiring process, and in 1967, the concept was expanded to include gender.

- The term “affirmative action” was first used in the U.S. when President John F. Kennedy signed Executive Order 10925 on 6 March 1961; it was used to promote actions that achieve non-discrimination. In 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson issued Executive Order 11246 which required government employers to take “affirmative action” to “hire without regard to race, religion and national origin.” In 1967, gender was added to the anti-discrimination list.

- Affirmative action is intended to promote the opportunities of defined minority groups within a society to give them access equal to that of the privileged majority population.

- It is often instituted in government and educational settings to ensure that certain designated “minority groups” within a society are included “in all programs.”

- The stated justification for affirmative action by its proponents is that it helps to compensate for past discrimination, persecution or exploitation by the ruling class of a culture, and to address existing discrimination.

- The implementation of affirmative action, especially in the U.S., is considered by its proponents to be justified by the belief that there is a disproportionate number of any minority group in any university, business, etc. (from wikipedia)

On the Supreme Court from BensGuide.gpo.gov:

- Approximately 7,500 cases are sent to the Supreme Court each year. Out of these, only 80 to 100 are actually heard by the Supreme Court. When a case comes to the Supreme Court, several things happen. First, the Justices get together to decide if a case is worthy of being brought before the Court. In other words, does the case really involve Constitutional or federal law? Secondly, a Supreme Court ruling can affect the outcome of hundreds or even thousands of cases in lower courts around the country. Therefore, the Court tries to use this enormous power only when a case presents a pressing constitutional issue. …

- The Supreme Court convenes, or meets, the first Monday in October. It stays in session usually until late June of the next year. When they are not hearing cases, the Justices do legal research and write opinions. On Fridays, they meet in private (in “conference”) to discuss cases they’ve heard and to vote on them. …

- Most cases do not start in the Supreme Court. Usually cases are first brought in front of lower (state or federal) courts. Each disputing party is made up of a petitioner and a respondent.

- Once the lower court makes a decisions, if the losing party does not think that justice was served, s/he may appeal the case, or bring it to a higher court. In the state court system, these higher courts are called appellate courts. In the federal court system, the lower courts are called United States District Courts and the higher courts are called United States Courts of Appeals.

- If the higher court’s ruling disagrees with the lower court’s ruling, the original decision is overturned. If the higher court’s ruling agrees with the lower court’s decision, then the losing party may ask that the case be taken to the Supreme Court. But … only cases involving federal or Constitutional law are brought to the highest court in the land.

EXPLANATION OF PROCEDURE FOR ORAL ARGUMENTS IN THE SUPREME COURT:

(from supremecourt.gov/visiting/visitorsguidetooralargument.aspx)

- A case selected for argument usually involves interpretations of the U. S. Constitution or federal law. At least four Justices have selected the case as being of such importance that the Supreme Court must resolve the legal issues.

- An attorney for each side of a case will have an opportunity to make a presentation to the Court and answer questions posed by the Justices. Prior to the argument each side has submitted a legal brief – a written legal argument outlining each party’s points of law. The Justices have read these briefs prior to argument and are thoroughly familiar with the case, its facts, and the legal positions that each party is advocating.

- Beginning the first Monday in October, the Court generally hears two one-hour arguments a day, at 10 a.m. and 11 a.m., with occasional afternoon sessions scheduled as necessary. Arguments are held on Mondays, Tuesdays, and Wednesdays in two-week intervals through late April (with longer breaks during December and February). The argument calendars are posted on the Court’s Website under the “Oral Arguments” link. In the recesses between argument sessions, the Justices are busy writing opinions, deciding which cases to hear in the future, and reading the briefs for the next argument session. They grant review in approximately 100 of the more than 10,000 petitions filed with the Court each term. No one knows exactly when a decision will be handed down by the Court in an argued case, nor is there a set time period in which the Justices must reach a decision. However, all cases argued during a term of Court are decided before the summer recess begins, usually by the end of June.

- During an argument week, the Justices meet in a private conference, closed even to staff, to discuss the cases and to take a preliminary vote on each case. If the Chief Justice is in the majority on a case decision, he decides who will write the opinion. He may decide to write it himself or he may assign that duty to any other Justice in the majority. If the Chief Justice is in the minority, the Justice in the majority who has the most seniority assumes the assignment duty.

(by Robert Barnes and William Branigin, The Washington Post) – The Supreme Court on Tuesday ruled by a 6-2 vote that Michigan voters had a right to ban affirmative action in their state via a ballot initiative which amended the state’s constitution.

(by Robert Barnes and William Branigin, The Washington Post) – The Supreme Court on Tuesday ruled by a 6-2 vote that Michigan voters had a right to ban affirmative action in their state via a ballot initiative which amended the state’s constitution.