Struggling New York Students Find a Future in Watchmaking

Daily News Article — Posted on October 31, 2014

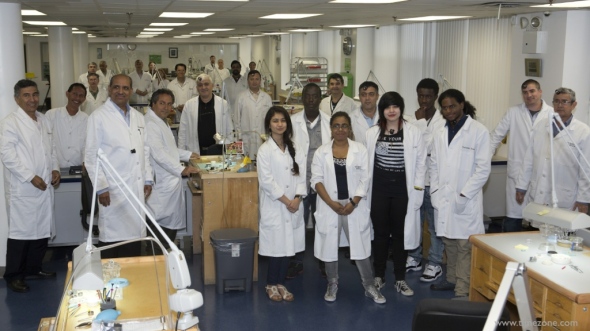

Since the program began in 2013, five students have accepted full-time internships with Tourneau

(by Sophia Hollander, The Wall Street Journal) – Clad in his white coat, Marcus Corbett might have been just another watchmaker at the Tourneau Repair Center in Long Island City, NY, tapping gently with a rubber-ended hammer to pop out near-microscopic pins.

But if his hooded sweatshirt didn’t give him away, his youthful face did: The 19-year-old from Bedford-Stuyvesant is a good two decades younger than any of the professional watch repairmen, known as watchmakers, in the facility.

Last year, Tourneau started a partnership with Manhattan Comprehensive Night and Day High School, which accepts transfer students who have struggled at, or aged out of, other schools. Classes meet twice a week for two months, giving students a taste of a field that can take years to master. So far, 25 students have completed the watch-repair program and six have landed jobs with the company. Only two have failed to finish.

In some ways, the partnership makes perfect sense: The aging watch industry is eager to attract younger apprentices. For students, it provides introduction to a potential career, in a field starved for new recruits.

Still, not all students could picture themselves tinkering with timepieces. “At first I was skeptical about it,” said Mr. Corbett, a member of the current nine-person class.

Last year, Mr. Corbett was forced to transfer from his Brooklyn high school after failing two Regents exams in senior year. He couldn’t focus and felt embarrassed asking questions or speaking in groups, he said. “I felt I was a kid with a hoodie on his head,” he said. “I thought I didn’t have much to say.”

But seeing the inside of watches sparked questions, he said. He was astonished by the sheer number of parts. He found a new ability to concentrate as he tinkered with the tiny pieces. Understanding watch innards has become as addictive as a new videogame, he said.

“Now I can take something that’s broken and fix it,” he said…. “It’s a good feeling to solve other people’s problems.”

Instead of disappearing with the emergence of time-telling smartphones, watch sales remain robust. About 1.2 billion watches were produced world-wide in 2013, according to the Federation of the Swiss Watch Industry.

But the number of watch-repair schools in the U.S. has plunged from around 50 in 1955 to six this year, says the American Watchmakers-Clockmakers Institute. In 2013, there were 2,840 people in the U.S. working in watch repair, including 300 in New York state, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

“If they didn’t make another watch, I think there’s enough work for another 50 years,” said Terry Irby, the 66-year-old technical director of service at Tourneau. But as timepieces continue to flood the market, the number of watchmakers has failed to keep pace, he said. “It’s a problem.”

Most worrisome, perhaps, is whether the ranks of workers will be replenished: About 15 years ago, the average age of members was around 60 to 65, estimated Fred White, president of the American Watchmakers-Clockmakers Institute. There is cause for hope, though, he said: Today, the average age is 46. “That shows that there are some younger people getting involved,” Mr. White said.

Chris Rene, left, works with shop foreman Johnny George at Tourneau.

Applicants to the Tourneau program are screened with short written essays and a simple dexterity test: Twist five paper clips into the numbers 1 through 5 using watchmaker tools.

On a recent afternoon, the students learned how to remove links and change batteries, while in an adjoining room professional watchmakers—who average 55 years old at Tourneau—hunched over similar tables, peering at specks of screws and gears.

“You don’t dare sneeze,” Mr. Irby said.

The high-security facility handles 200 watches a day, with many pieces valued at $36,000 or more, Mr. Irby said.

Today’s watches are more intricate than ever, tracking everything from moon phases to perpetual calendars. Some include chronometers and monitor multiple time zones.

It can take a skilled watchmaker an hour to deconstruct a watch and three hours to reassemble it – “if everything goes well,” Mr. Irby said.

Entry-level positions earn in the mid-$30,000s, said Mr. Irby, but experienced watchmakers can earn up to $100,000.

Pablo Gonzalez, 19, enrolled in the program’s first class last spring. He was flunking his courses, clashed with his parents and hung out “with a bad group of kids,” he said. “I was really going downhill,” he said. “Everything was going wrong.”

But he found peace in the three-dimensional puzzle of hundreds of miniature watch pieces.

He began experimenting with other activities, learning how to play handball and rediscovering his love of skateboarding.

“It makes you confident about what other things you could do,” said Mr. Gonzalez, who was one of the first program graduates hired by Tourneau.

Now he wears his hair pulled back in a ponytail, with a tie visible under his white coat. He was recently selected to be one of six Tourneau employees traveling to Dallas next month to study Cartier quartz watches.

Mr. Gonzalez praised the calm that can be found in the quiet order of the perfectly fitting gears; the pleasure that comes from cleaning a scuffed watch and making it gleam like new; the power in taking something broken and being viewed as the person who can fix it.

“I love that feeling of accomplishment,” he said. “I love making it work.”

Copyright 2014 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Reprinted here for educational purposes only. May not be reproduced on other websites without permission from The Wall Street Journal. Visit the website at wsj .com

Questions

NOTE: Today's Daily News Article is a human interest story. In journalism, a human interest story is a feature story that discusses a person or people in an emotional way. It presents people and their problems, concerns, or achievements in a way that brings about interest, sympathy or motivation in the reader or viewer. Human interest stories may be "the story behind the story" about an event, organization, or otherwise faceless historical happening, such as about the life of an individual soldier during wartime, an interview with a survivor of a natural disaster, a random act of kindness or profile of someone known for a career achievement. (wikipedia)

1. The Tourneau Repair Center is a high-security facility that handles 200 watches a day, with many pieces valued at $36,000 or more. Describe the partnership between Tourneau and Manhattan Comprehensive Night and Day High School.

2. How does the partnership benefit Tourneau?

3. How has the program changed Marcus Corbett’s life? Be specific.

4. a) What is surprising about watch sales in 2014?

b) How does the job market look for a skilled watchmaker?

5. What has the program done for Pablo Gonzalez? What does he say about it?

6. What type of technical training programs does your high school offer?