States face decision day on saving trains

Daily News Article — Posted on September 16, 2013

(by Josh Mitchell, The Wall Street Journal) INDIANAPOLIS – Residents of this capital city looking to visit Chicago can board an Amtrak train for a five-hour journey that costs about $24 – a price that excludes the $80-per-ticket in federal subsidies that keep the service running.

(by Josh Mitchell, The Wall Street Journal) INDIANAPOLIS – Residents of this capital city looking to visit Chicago can board an Amtrak train for a five-hour journey that costs about $24 – a price that excludes the $80-per-ticket in federal subsidies that keep the service running.

Or they can take a bus for about $24 to $37, with no direct government subsidy, a trip scheduled at a bit more than three hours.

That divide is driving a debate in Indiana and 18 other states about whether to drop expensive passenger-rail services, a defining moment for a mode of transportation that shaped the U.S. for a century and a half.

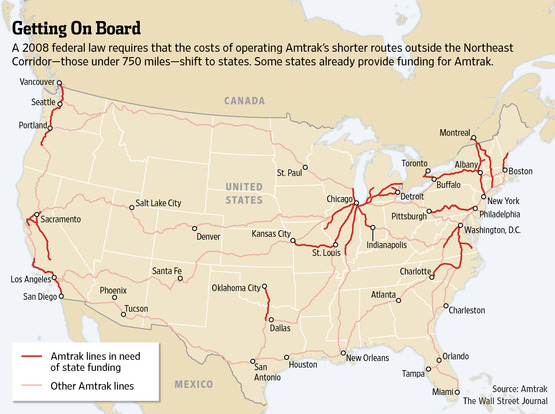

Amtrak’s Hoosier State service, a 196-mile run from Indianapolis to Chicago, travels through the state’s cornfields and small towns four times a week. Congress, under a 2008 law, cut off funding for that line and other short Amtrak routes across the U.S. starting Oct. 1 [2013]. Amtrak will require Indiana to pony up $3 million a year to maintain the train, sparking a political tussle among small-town mayors, state budget hawks and fans of passenger rail. [Click here for a map of Amtrak service in the U.S.]

If Indiana balks, service between Indianapolis and Chicago wouldn’t disappear completely: Amtrak’s three-day-a-week Cardinal train from New York to Chicago would continue to make the same stops. But ending the Hoosier State would eliminate service the four other days of the week.

Supporters say passenger-rail service helps boost local economies, and that daily service is essential to keeping trains a viable alternative to airplanes and cars.

But critics say the short routes waste tax dollars on a small number of passengers, money they say would be better spent on things like fixing roads and upgrading schools.

Indiana State Sen. Jim Banks, a Republican whose rural district lacks Amtrak service, said the Hoosier State has limited economic benefit, serving an average of 180 passengers each day it operates, including many who instead could take a bus.

“Whether in debates on the floor in the Senate or conversations over a beer with a friend, everything is always an anecdotal argument in favor of it,” Mr. Banks said. “I’ve never seen evidence of a return on investment that would occur.”

Eighteen other states face the same decision. Many already provide at least some funds for short-distance Amtrak routes. The 2008 law effectively requires those states to boost their subsidies to make up for cuts in federal funding. At least five states have reached agreements with Amtrak to maintain routes, and many others have taken steps to do so.

The debate comes as passenger rail nationwide – once a centerpiece of the Obama administration’s plans to modernize transportation infrastructure – takes a hit from tighter government spending.

In California, plans for a bullet train from San Francisco to Los Angeles have been set back repeatedly by mounting construction costs and residential opposition. In late 2010, newly elected GOP governors in Ohio and Wisconsin returned passenger-rail funds to the Obama administration, calling the projects wasteful and citing their concern of being saddled with operating costs. Florida’s governor in 2011 canceled plans for a high-speed rail line between Tampa and Orlando, citing costs.

To decide the fate of the Hoosier State line, Indiana’s Republican governor, Mike Pence, is awaiting a cost-benefit analysis from a private firm, due in late September. He hasn’t said which way he leans.

Since at least the 1880s, save for a few brief periods, one railroad or another has offered daily service between Indianapolis and Chicago, according to Craig Sanders, author of “Amtrak in the Heartland.” …

Amtrak spokesman Marc Magliari said the biggest expenses of the Hoosier State train are leasing the track from the private freight company that owns it, along with labor and fuel. The train’s slow speed—while it hits 79 miles per hour it averages about 39 mph, including station stops—reflects the condition of the track and lack of technology, such as updated signals, he said. Amtrak says boosting investment would improve service and increase ridership.

Background

"This is history," said Patricia Dean, a 60-year-old retired custodian, as she settled into a seat recently on a half-empty Amtrak car out of Chicago, headed to her hometown of Indianapolis. "The first time I ever remember traveling, with my mom, it was on the train." Ms. Dean, returning from a family reunion, said the train is more spacious, quieter and cleaner than a bus.

One recent evening, the passengers included a group of friends from Indianapolis who had spent the weekend in Chicago to catch a Cubs game; a Chicago man riding the train for the first time to buy a car from a relative in Indiana; and Michael Burch, who was returning to Indiana after visiting Boulder, Colo.

Mr. Burch, who recently moved to Crawfordsville, Ind., to be an assistant professor at Wabash College, said he uses the service several times a month to fly out of Chicago's O'Hare airport. He said he supports not just maintaining existing service but increasing the trips between the cities, which he said would lead to more ridership and revenue. "To me, [rail] transportation is a public good, a public need," he said, adding that small towns on the route lack bus service to Chicago. (from the WSJ article above)