Andrew Langlois with Akira and his ballot.

redo Jump to...

print Print...

(by Scott Malone, Reuters) BOSTON — New Hampshire officials on Tuesday will try to persuade a federal appeals court that a 2014 law banning voters from posting online photos of their ballots on election day does not violate the U.S. right to free speech.

The state banned the practice two years ago in response to the growing trend of voters taking selfies with their filled-in ballots and posting them on social media sites, including Facebook and Twitter.

Opponents of the ban quickly charged that it violated the free-speech protections of the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. A New Hampshire voter sued in October 2014 after posting online a photo of his ballot, on which he filled in the name of his dog as a sign of displeasure over his choices in the 2014 Republican primary for the U.S. Senate.

U.S. District Judge Paul Barbadoro agreed with that voter and his fellow plaintiffs, pronouncing the law unconstitutional in August 2015.

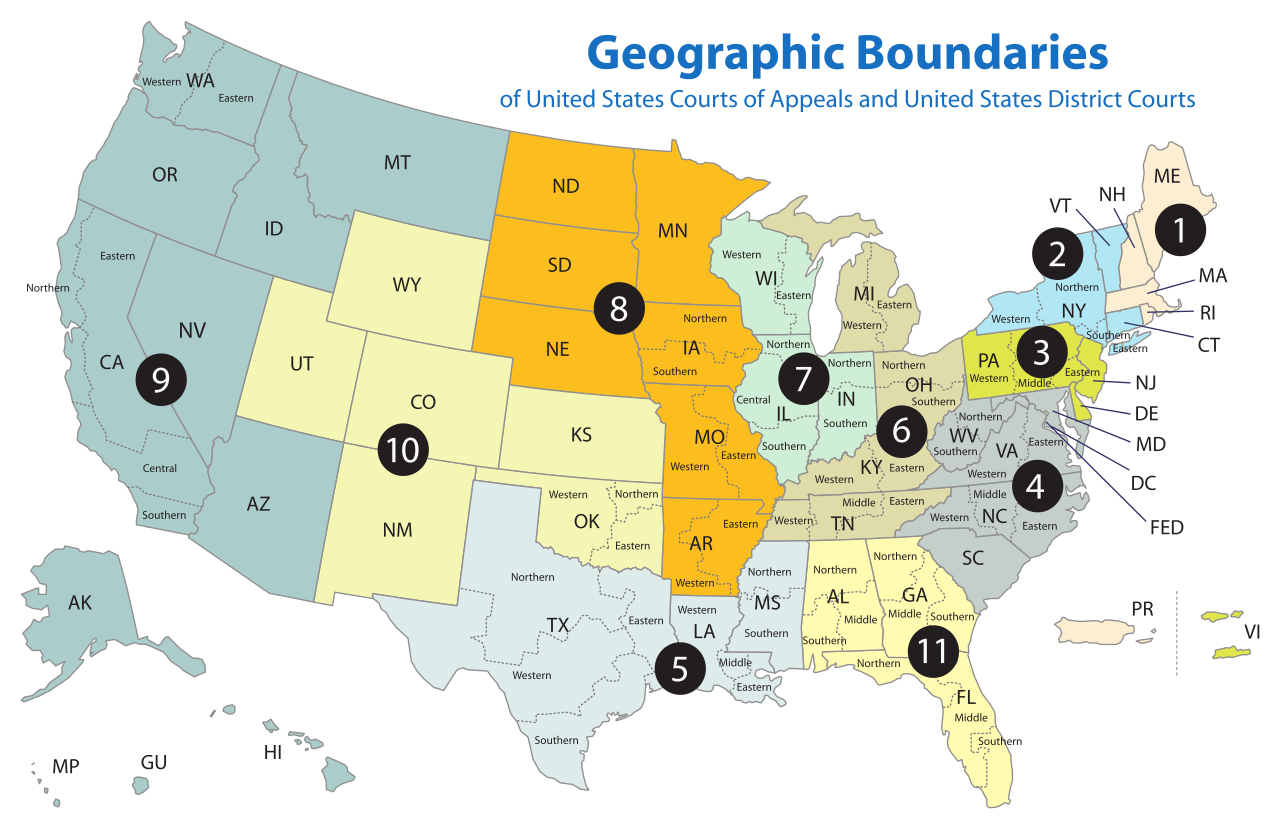

The state appealed the following month, setting the stage for Tuesday’s arguments before the First Circuit of the U.S. Court of Appeals in Boston.

New Hampshire argues that having the right to take a photo of a filled-in ballot and post it publicly risks a return to the problem of vote-buying, which ran rampant in the 19th century, when machine politicians [a politician who belongs to a small clique that controls a political party for private rather than public ends] secured votes through cash or liquor. [Stephen LaBonte of the New Hampshire attorney general’s office wrote in the March brief New Hampshire has a compelling interest in trying to prevent potential problems and ensuring “purity and integrity of our elections by protecting the longstanding tradition of the secret ballot.”]

“Imagine a less fortunate ’18-year-old, newly minted voter’ who has been informed that if she does not vote as she has been instructed, she will lose the job she needs to pay her college tuition,” state officials wrote in court papers supporting the ban.

Opponents of the measure contend ballot-box selfies are a form of political speech familiar to first-time voters, akin to the photos they post of themselves on vacation, at concerts or with friends.

“Any activity that increases civic engagement among younger voters should be recognized as a universal social good,” wrote the New England First Amendment Coalition and the Keene Sentinel newspaper in a brief supporting the challenge to the law, which allows for a fine of up to $1,000 for ballot selfies.

Reprinted here for educational purposes only. May not be reproduced on other websites without permission from Thomson Reuters. Visit the website at Reuters.com.

Questions

1. The first paragraph of a news article should answer the questions who, what, where and when. List the who, what, where and when of this news item. (NOTE: The remainder of a news article provides details on the why and/or how.)

2. Why did New Hampshire pass the 2014 law?

3. Three New Hampshire voters are challenging the law. One of the voters, Andrew Langlois, thought someone was playing a joke on him when he received a call from the New Hampshire attorney general’s office telling him he was under investigation for posting a ballot selfie on social media, according to the lawsuit. Mr. Langlois had written in the name of his dead dog, Akira, snapped a photo of the ballot and posted it on Facebook, triggering the investigation, according to court documents. Mr. Langlois could face a fine of $1,000, if the law is reinstated. The investigation of Mr. Langlois and the other two plaintiffs is on hold pending the outcome of the First Circuit case.

On what grounds did these voters sue?

4. What argument is New Hampshire using to defend the law?

5. From a September 11 Wall Street Journal article:

A lower federal court in New Hampshire pronounced the law unconstitutional in an August 2015 ruling, finding state officials failed to provide a single example of a ballot selfie used to facilitate vote buying or coercion. New Hampshire appealed the ruling to the First Circuit.

New Hampshire Secretary of State William Gardner, whose office pushed for the ban and who is named as the defendant in the case, acknowledged in legal papers there was “little evidence of vote buying and voter coercion schemes currently being executed with the use of digital imagery.”

But New Hampshire has a compelling interest in trying to prevent potential problems and ensuring “purity and integrity of our elections by protecting the longstanding tradition of the secret ballot,” his lawyer, Stephen LaBonte of the New Hampshire attorney general’s office, wrote in the March brief.

Lawyers for three New Hampshire voters challenging the 2014 law asked the First Circuit to disregard the state’s “apocalyptic” speculation about the potential for ballot selfies to fuel corrupt elections.

The law, wrote lawyers Gilles Bissonnette and William Christie, “fails to realize the critical importance of online political speech under the First Amendment as well as to American culture.”

New Hampshire was the first state to prohibit ballot selfies, but many states have older laws that forbid voters from showing marked ballots or the face of voting machines to others.

Since 2011, at least five states—Maine, Oregon, Utah, Arizona, and California—have carved out exceptions that allow voters to share photos of their ballots, according to the American Civil Liberties Union of New Hampshire, which is representing the voters in the 2014 lawsuit.

How do you think the court should rule? Is it possible that selfies in the voting booth could compromise the purity and integrity of our elections? Explain your answer.

6. Ask a parent: would you take a selfie at the ballot box? Why or why not?

Background

THE U.S. COURT SYSTEM: There are two separate court systems in America:

- The federal court system deals with issues of law relating to those powers expressly or implicitly granted to it by the U.S. Constitution, while

- The state court systems deal with issues of law relating to those matters that the U.S. Constitution did not give to the federal government or explicitly deny to the states. (read more at the U.S. Courts website)

from BensGuide.gpo.gov:

- Most cases do not start in the Supreme Court. Usually cases are first brought in front of lower (state or federal) courts. Each disputing party is made up of a petitioner and a respondent.

- Once the lower court makes a decisions, if the losing party does not think that justice was served, s/he may appeal the case, or bring it to a higher court.

- In the state court system, these higher courts are called appellate courts.

- In the federal court system, the lower courts are called U.S. District Courts and the higher courts are called U.S. Courts of Appeals.

- If the higher court’s ruling disagrees with the lower court’s ruling, the original decision is overturned. If the higher court’s ruling agrees with the lower court’s decision, then the losing party may ask that the case be taken to the Supreme Court. But … only cases involving federal or Constitutional law are brought to the highest court in the land [the Supreme Court].

The Courts of Appeals

Each of the 12 regional circuits has one U.S. court of Appeals that hears appeals to decisions of the district courts located within its circuit and appeals to decisions of federal regulatory agencies. The Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit has nationwide jurisdiction and hears specialized cases like patent and international trade cases.

For a Circuit Court of Appeals map, go to uscourts.gov/court_locator.aspx.

- For brief information on district court and court of appeals, go to uscourts.gov

- To follow the case, visit the First Circuit Court of Appeals website

Daily “Answers” emails are provided for Daily News Articles, Tuesday’s World Events and Friday’s News Quiz.