Justice Department set to free 6,000 prisoners

Daily News Article — Posted on October 8, 2015

(by Sari Horwitz, The Washington Post) – The Justice Department is set to release about 6,000 inmates early from prison – the largest one-time release of federal prisoners – in an effort to reduce overcrowding and provide relief to drug offenders who received harsh sentences over the past three decades, according to U.S. officials.

The inmates from federal prisons nationwide will be set free by the department’s Bureau of Prisons between Oct. 30 and Nov. 2. About two-thirds of them will go to halfway houses and home confinement before being put on supervised release. [About one-third of the 6,000 inmates are non-citizens so they will be turned over to U.S. Immigration Custom Enforcement officials for deportation proceedings, according to one Justice Department official.]

The early release follows action by the U.S. Sentencing Commission (USSC) – an independent agency that sets sentencing policies for federal crimes – that reduced the potential punishment for future drug offenders last year and then made that change retroactive [taking effect from a date in the past].

The commission’s action is separate from an effort by President Obama to grant clemency to certain nonviolent drug offenders, an initiative that has resulted in the early release of 89 inmates.

The panel estimated that its change in sentencing guidelines eventually could result in 46,000 of the nation’s approximately 100,000 drug offenders in federal prison qualifying for early release. The 6,000 figure, which has not been reported previously, is the first tranche in that process.

“The number of people who will be affected is quite exceptional,” said Mary Price, general counsel for Families Against Mandatory Minimums, an advocacy group that supports sentencing reform.

The Sentencing Commission estimated that an additional 8,550 inmates would be eligible for release between this Nov. 1 and Nov. 1, 2016.

The releases are part of a shift in the nation’s approach to criminal justice and drug sentencing that has been driven by a bipartisan consensus that mass incarceration has failed and should be reversed.

Along with the commission’s action, the Justice Department has instructed its prosecutors not to charge low-level, nonviolent drug offenders who have no connection to gangs or large-scale drug organizations with offenses that carry severe mandatory sentences.

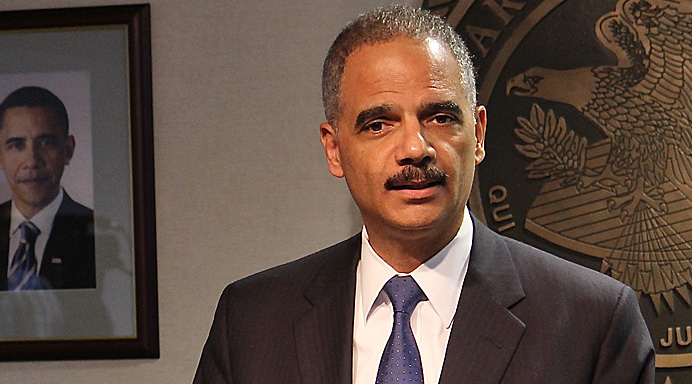

The U.S. Sentencing Commission voted unanimously for the reduction last year after holding two public hearings in which members heard testimony from then-Attorney General Eric H. Holder Jr., federal judges, federal public defenders, state and local law enforcement officials, and sentencing advocates.

Holder supported the change, but he proposed more restrictive criteria that would exclude people who had used weapons or had significant criminal histories. But the Sentencing Commission decided to leave the decisions to individual judges.

In August 2013, then-Attorney General Eric Holder called for scaled-back drug sentences

Congress did not act to disapprove the change to the sentencing guidelines, so it became effective on Nov. 1, 2014. The commission then gave the Justice Department a year to prepare for the huge release of inmates.

The policy change is referred to as “Drugs Minus Two.” Federal sentencing guidelines rely on a numeric system based on different factors, including the defendant’s criminal history, the type of crime, whether a gun was involved and whether the defendant was a leader in a drug group.

The sentencing panel’s change decreased the value attached to most drug-trafficking offenses by two levels, regardless of the type of drug or the amount.

An average of about two years is being shaved off eligible prisoners’ sentences under the change. Although some of the inmates who will be released have served decades, on average they will have served 8 1/2 years instead of 10 1/2 , according to a Justice Department official.

“Even with the Sentencing Commission’s reductions, drug offenders will have served substantial prison sentences,” Deputy Attorney General Sally Yates said. “Moreover, these reductions are not automatic. Under the commission’s directive, federal judges are required to carefully consider public safety in deciding whether to reduce an inmate’s sentence.”

In each case, inmates must petition a judge, who decides whether to grant the sentencing reduction. Judges nationwide are granting about 70 sentence reductions per week, Justice Department officials said. Some of the inmates already have been sent to halfway houses.

In some cases, federal judges have denied inmates’ requests for early release. For example, U.S. District Judge Royce C. Lamberth recently denied requests from two top associates of Rayful Edmond III, one of [Washington D.C.’s] most notorious drug kingpins.

Federal prosecutors did not oppose a request by defense lawyers to have the associates, Melvin D. Butler and James Antonio Jones, released early in November. But last month, Lamberth denied the request, which would have cut about two years from each man’s projected 28 1/2 -year sentence.

“The court struggles to understand how the government could condone the release of Butler and Jones, each convicted of high-level, sophisticated and violent drug-trafficking offenses,” Lamberth wrote. The Edmond group imported as much as 1,700 pounds of Colombian cocaine a month into the city in the 1980s, according to court papers.

Critics, including some federal prosecutors, judges and police officials, have raised concerns that allowing so many inmates to be released at the same time could cause crime to increase. …

Spencer S. Hsu contributed to this report.

Reprinted here for educational purposes only. May not be reproduced on other websites without permission from The Washington Post. For the original article, visit washingtonpost .com.

Background

From KOCO News:

- The releases come amid a surge in murders and violent crimes in many cities around the country -- a trend that FBI Director James Comey noted during a recent press briefing at FBI headquarters. Comey told reporters no one seems to be able to explain increases of 30% to 50% in murders in a wide variety of cities with little in common.

"Something very worrisome is going on," he said Thursday. He added that his concern will cause him to be "thoughtful" about ongoing moves to reform the nation's criminal justice system.

From the NY Times:

- In April 2014, the United States Sentencing Commission reduced the penalties for many nonviolent drug crimes.

- That summer it said those guidelines could be applied retroactively to many prisoners serving long drug sentences.

- Eric H. Holder Jr., the attorney general at the time, had lobbied the sentencing commission to make the changes.