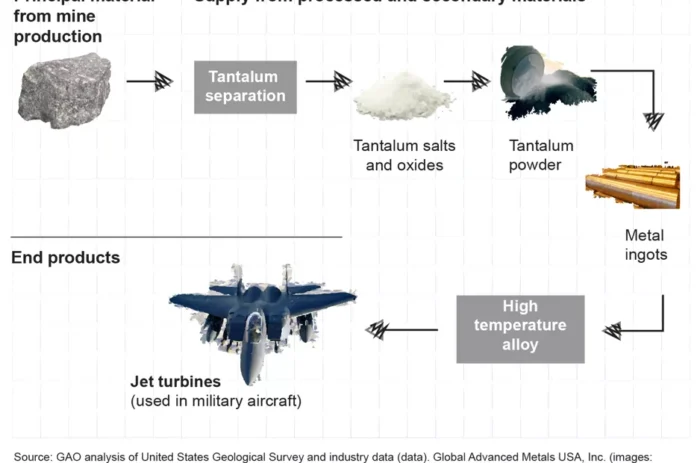

Illustration of assassin John Wilkes Booth running to the stage after shooting Abraham Lincoln at Ford's Theatre, Washington DC, April 14, 1865. (Kean Collection/Getty Images)

redo Jump to...

print Print...

(New York Post) – 150 years ago [yesterday], President Abraham Lincoln was enjoying a play at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, DC, when an assassin shot him at point-blank range in the back of the head. He died the next morning, the day this edition of The New York Post was published (see “Background” below for complete reports). At that time, The Post – then midway through its 64th year of operation – was printed for evening distribution and was called The Evening Post.

The president died just 42 days after being sworn in for his second term and six days after Gen. Robert E. Lee, commander of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, surrendered to Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant and the Union Army of the Potomac, at Appomattox Court House, Va., effectively ending the American Civil War.

The assassination of Lincoln was part of a larger plot to eliminate the president, as well as Vice President Andrew Johnson and Secretary of State William H. Seward. But the rest of the plot failed. The vice president’s would-be assassin chickened out at the last minute. Seward was stabbed repeatedly in the face and neck as he lay in his bed at home, but recovered from his injuries.

Lincoln was the first of four American presidents slain by assassins, the others being President James Garfield (1881), President William McKinley (1901) and President John F. Kennedy (1963).

Yesterday [April 14, 2015], The Post republished, word-for-word, its coverage of President Lincoln’s assassination, first printed the day he died in a first-floor bedroom at a boarding house across the street from the theater where the fatal shot was fired. (see text under “Background” below)

A prominent stage actor, John Wilkes Booth, armed with a Philadelphia Derringer pistol, fired the shot.

Lincoln died less than 9 1⁄2 hours later – at 7:22 a.m. on April 15, 1865. He was 56 years of age.

Reprinted here for educational purposes only. May not be reproduced on other websites without permission from the New York Post.

Questions

1. a) Who shot President Lincoln?

b) What evidence did the Post (known as The Evening Standard then) provide in its reports to back up the belief that this man was the assassin?

2. Where and when was he shot?

3. Why was he assassinated?

4. In addition to printing Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton’s reports on President Lincoln, the NY Post (then called The Evening Post) published “Particulars of the Assassination” which is posted in “Background” below.

Read this original report.

Narrative journalism is the interpretation of a story and the way in which the journalist portrays it, be it fictional or non-fictional. In easier words, it tells a story.

What do you learn from this narrative report that you did not already know about President Lincoln’s assassination?

5. Read the excerpt from WSJ commentary on Lincoln’s assassination “A President Who Lived and Died for Liberty” (see “Background” below). What most surprises you from this excerpt, or with which assertion made by the writers do you most agree? Explain your answer.

Background

The Post republished, word-for-word, its coverage of President Lincoln’s assassination, first printed the day he died. NOTE that there are several typos in this original text. We have not made any corrections but left them exactly as originally published. Read the reports below:

President Lincoln has been shot

Dispatches from Secretary Stanton

Abraham Lincoln was assassinated in Ford’s Theater in Washington at half-past nine o’clock last night, and at about the same time Secretary Seward, was attacked in his sick room and his throat cut.

Particulars are given below.

First Despatch from Secretary Stanton:

War Department, Washington, April 15 – 1:30 a.m.

Major General Dix, News York:Last evening at about 9:30 o’clock, at Ford’s Theatre, the President, while sitting in his private box with Mrs. Lincoln, Mrs. Harris and Major Rathbun, was shot by an assassin, who suddenly entered the box and approached behind the President.

The assassin then leaped upon the stage, brandishing a large dagger or knife, and made his escape in the rear of the theatre.

The pistol ball entered the back of the President’s head, and penetrated nearly through the head. The wound is mortal.

The President has been insensible ever since it was inflicted, and is now dying.

About the same hour an assassin, whether the same or not, entered Mr. Seward’s apartments, and, under pretense of having a prescription, was shown to the Secretary’s sick chamber. The assassin immediately rushed to the bed and inflicted two or three stabs on the throat and two in the face.

It is hoped the wounds may not be mortal. My apprehension is that they will prove fatal.

The nurse alarmed Mr. Frederick Steward, who was in an adjoining room, and he hastened to the door of his father’s room, when he met the assassin, who inflected upon his one or more dangerous wounds. The recovery of Frederick Seward is doubtful.

It is not probable that the President will live through the night.

General Grant and wife were advertised to be at the theatre this evening, but he started to Burlington at six o’clock this evening.

At a Cabinet meeting, at which General grant was present, the subject of the state of the country and the prospect of a speedy peace were discussed. The President was very cheerful and hopeful and spoke very kindly of General Lee and others of Confederacy, and the establishment of government in Virginia.

All the members of the Cabinet, except Mr. Seward, are nor in attendance upon the President.

I have seen Mr. Seward, but he and Frederick were both unconscious.

Edwin M. Stanton, Secretary of War

Second Despatch from Secretary Stanton:

War Department, Washington, April 15 – 3:00 a.m.

Major-General Dix, New York:The President still breathes, but is quite insensible, as he has been ever since he was shot. He evidently did not see the person who shot him, but was looking on the stage, as he was approached from my behind.

Mr. Seward has rallied, and it is hoped he may live.

Frederick Seward’s condition is very critical.

The attendant who was present was shot through the lungs, and is not expected to live.

The wounds of Major Seward are not serious.

Investigation strongly indicates J. Wilkes Booth as the assassin of the President. Whether it was the same or a different person that attempted to murder Mr. Seward remains in doubt.

Chief Justice Cartter is engaged in taking the evidence.

Every exertion has been made to prevent the escape of the murder. His horse has been found on the road near Washington.

Edwin M. Stanton, Secretary of War

Particulars of the Assasination

The following are the particulars of the assassinations, as gathered from the different reports:

“Washington, April 14 – President Lincoln and wife, with other friends, this evening visited Ford’s Theatre for the purpose of witnessing the performance of the ‘American Cousin’.”

“It was announced in the papers that General grant would also be present, but he took the late train of cars from New Jersey.”

“The theatre was densely crowded, and everybody seemed delighted with the scene before a temporary pause for one of the actors to enter, a sharp report of a pistol was heard, which merely attracted attention, but suggesting nothing serious, until a man rushed to the front of the President’s box, waving a long dagger in his right hand, and exclaiming ‘Sic semper tyrannis’, and immediately leaped from the box, which was in the second tier. To the stage beneath, and ran across to the opposite side, making his escape amid the bewilderment of the audience from the rear of the theatre, and mounting a horse, fled.

“Screams of Mrs. Lincoln first disclosed the fact to the audience that the President had been shot, when all present rose to their feet, rushing towards the stage, main exclaiming ‘Hang Him! hang him!

“The excitement was of the wildest possible description, and of course there was an abrupt termination of the theatrical performance.

There was a rush towards the President’s box, when cries were heard: ‘Stand back and give him air.’ ‘Has any one stimulants.’ On a hasty examination, it was found that the president had been shot through the head, above and back of the temporal bone, and that some of the brain was oozing out. He was removed to a private house opposite of the theater, and the Surgeon-General of the Army, and other surgeons sent for to attend his condition.

“On the examination of the private box blood was discovered on the back of the cushioned rocking-chair on which the President had been sitting, also on the partition and on the floor. A common single-barreled pocket pistol was found on the carpet.

“A military guard was placed in front of the private residence to which the President had been conveyed.” An immense crowd was in front of it, all deeply anxious to learn the condition of President. It had been previously announced that the wound was mortal, but all hoped otherwise. The shock to the community was terrible.

“The President is in a state of syncope, totally insensible, and breathing slowly. The blood oozed from the wound at the back of his head. The surgeons exhausted every effort of medical skill, but all hope was gone. The parting of his family with the dying President is too sad for description.”

“At midnight the Cabinet, with Messrs. Sumner Colfax and Farnsworth, Judge Curtis, Governor Oglesby, General Meigs, Colonel Hay, and a few person friends, with Surgeon General Barnes and his immediate assistants were around his bedside.

“The President and Mrs. Lincoln did not start for the theatre until fifteen minutes after eight o’clock. Speaker Colfax was at the White House at the time, and the President stated to him that he was going, though Mrs. Lincoln had not been well, because the papers had announced that General Grant and they were to be present, as General Grant had gone north, he did not wish the audience to be disappointed.

“He went with apparent reluctance and urged Mr. Colfax to go with him, but the gentleman had made other engagements, and with Mr. Ashmun, of Massachusetts, bid him goodbye.”

A special dispatched to the Herald says:

“When the fatal shot was fired, Mrs. Lincoln, who was alongside of her husband, exclaimed, ‘Oh! Why didn’t they shot me- why didn’t they shoot me?

“There is evidence that Senator Stanton was also marked for assassination. Oh receipt of intelligence of the War Department of the attack on the President, two employees of the Department we sent to summon the secretary. Just as they approached his house, a man jumped out from behind a tree box in front of the house and ran away. It is well known for the Secretary to go from the department to his house between nine and twelve P.M, and usually unattended. I supposed that the assassin intended to shoot him as he entered the house, but failed from the tact that Mr. Stanton remained at home during the evening.”

“The circumstantial evidence is very strong that J. Wilkes Booth was the one that shot the President. Several parties are well acquainted from the box, are positive that he is the man. It was also reported that Booth’s horse was saddled at the side door of the theater and was rode off by the assassin. If he is the man, it is impossible for him to escape. The horse of the man who made the attack on Secretary Seward has been found near the Lincoln hospital, bathed in sweat, and with blood upon the saddle cloths.”

The Attack Upon Mr. Seward

When the excitement at the theatre was at its wildest height, reports were circulated that Secretary Seward had also-been assassinated.

On reaching the gentleman’s residence a crowd and a military guard were found at the door, and on entering it ascertained that the reports were based on truths.

Everybody there was so excited that scarcely an intelligible word could be gathered, but the facts are substantially as follows:

About 10 o’clock a man rang the bell, and the call having been answered by a colored servant, he said he had come Dr. Verdi, Secretary Seward’s family Physician, with a prescription , at the same time holding a piece of small folded paper, and saying, answer to the refusal that he must see the Secretary, as he was entrusted with particular directions concerning the medicine.

He still insisted on going up, although repeatedly informed that no one could enter the chamber. The man pushed the servant aside, and walked heavily towards the Secretary’s room, and was then met by Mr. Fredrick Seward of whom he demanded to see the Secretary, making the same representation which he did to the servant.

What further passed in the way of colloquy is not known; but the man struck him on the head with a “billy,” severely injuring the skull and felling him senseless. The assassin then rushed into the chamber and attacked Major Seward, pay master of the United States army and Mr. Hansel, a messenger of the State Department, and two male nurses, disabling them all. He then rushed upon the Secretary, who was lying in bed in the same room, and inflicted three stabs in the neck, but severing, it is thought and hoped, no arteries, though he bled profusely.

Another Account

The correspondent of the Times writes:

“A stroke from Heaven laying the whole of the city instant ruins could not have startled us as did the word that broke Ford’s Theatre a half hour ago, that the President had been shot. It flew everywhere in five minutes, and set five thousand people in swift and excited motion on instant.

“It is impossible to get at the full facts of the case, but it appears that a young man entered the President’s box from the theatre, during the last act of the play of “Our American Cousin,” with pistol in hand. He shot the President in the head, and instantly jumped from the box upon the stage, and immediately disappeared through the side scenes and rear of the theatre, brandishing a dirk knife and dropping a kid glove on the stage.

“The audience heard the shot, but supposing it fired in the regular course of the play, did not heed it till Mrs. Lincoln’s scream drew their attention. The whole affair occupied scarcely half a minute, and then the assassin was gone. As yet he has not been found.”

“The President’s wound is reported mortal. He was at once taken into the house opposite the theatre.”

“As if the horror was not enough almost the same moment the story ran through the city that Mr. Seward had been murdered in his bed.”

“Inquiry showed this to be far true also it appears is appears a man wearing a light coat, dark pantaloons, slouch hat, called and asked to see Mr. Seward, and was shown to his room He delivered to Major Seward, who sat near his father what purported to be a physician’s prescription, turned and with one stroke cut Mr. Seward’s throat as he lay on his bed, inflicting a horrible wound, but not severing the jugular vein, and not producing a mortal wound.

“In the struggle that followed Major Seward was also badly, but not seriously, wounded in several places. The assassin rushed down stairs, mounted the fleet horse on which he came, drove his spurs into him and dashed away before anyone could stop him.”

“Reports have prevailed that an attempt was also made on the life of Stanton.”

“Midnight – The President is reported dead. Cavalry and infantry are scouring the city in every direction for the murderous assassin, and the city is overwhelmed with excitement. Who the assassins were, no one knows, though every body supposes them to have been rebels.”

The Following is from an April 13, 2015 WSJ commentary on Lincoln’s assassination “A President Who Lived and Died for Liberty” (by James L. Swanson and Michael F. Bishop):

One hundred and fifty years later, what does the death of Abraham Lincoln mean?

It is obvious but too often overlooked that Lincoln died a martyr for civil rights. Already the prime instrument of the abolition of slavery, through the Emancipation Proclamation and the 13th Amendment he masterfully maneuvered through Congress, Lincoln in the last speech of his life called for voting rights for black Americans. Among the crowd at the White House, as the president spoke from a second-floor window, was John Wilkes Booth. Incandescent with rage and spewing racial hatred, he resolved to assassinate Lincoln. Seventy-two hours later, he fired the fatal shot.

The first presidential assassination affirmed the enduring strength of our form of government. By April 1865 American institutions had survived their severest trial, but the constitutional fabric of the nation was further frayed in the aftermath of Lincoln’s murder. The Union, though, would endure; the United States would assume its place as the dominant world power. American democracy transcended any one man, even one as great as Lincoln.

And yet, the death of Lincoln did grave harm to the Union he had given his life to save. Not least of the tragedies to befall the nation that day was the accession to power of the coarse and inept Vice President Andrew Johnson, who himself might have died had the assassin dispatched to murder him not lost his nerve. Crude and inflexible, Johnson botched the reconstruction of the nation. Lincoln had rightly considered Reconstruction “the greatest question ever presented to practical statesmanship,” but his successor lacked his principled pragmatism.

Eager to usher Confederate states back into the Union, and himself a racist, Johnson was indifferent to the callous treatment of newly freed slaves. The eventual reconciliation of North and South came at the expense of civil rights for black Americans, which poisoned race relations for a century.

The death of Lincoln reminds us that leadership matters, and that much depends on the occupant of the White House. Lincoln lived and died for liberty, union and equal rights for all people. With every fiber of his being, Abraham Lincoln believed in American greatness and exceptionalism.

As we mourn him on the anniversary of his death, we must do more than yearn for great leaders like Lincoln. We must cultivate and elect them.

Mr. Swanson, senior legal scholar at the Heritage Foundation, is the author of the excellent book: “Manhunt: The 12-Day Chase for Lincoln’s Killer.” Mr. Bishop has held several posts on Capitol Hill and in the White House, and is the former executive director of the Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission.

Resources

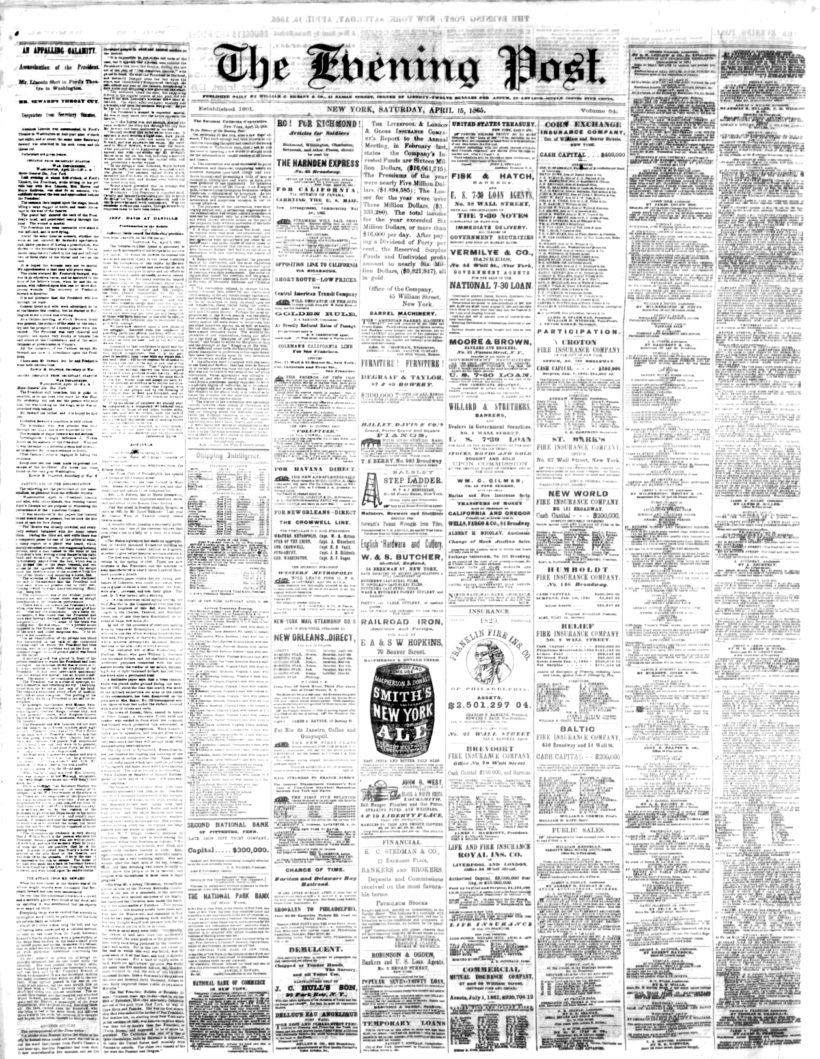

The New York Post — previously “The Evening Post” — Front page from April 15, 1865:

The New York Post — previously “The Evening Post” — Front page from April 15, 1865.

Daily “Answers” emails are provided for Daily News Articles, Tuesday’s World Events and Friday’s News Quiz.