Germany: 25th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall

Daily News Article — Posted on November 7, 2014

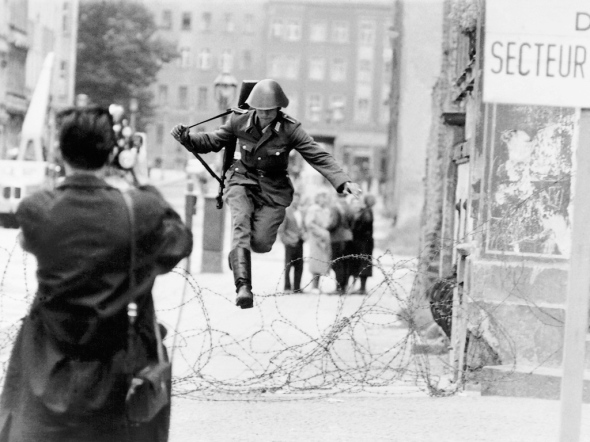

Many thousands of East German border guards also tried to escape, and around 2,500 succesfully made it to the West. However, 5,500 were captured in the attempt and received an average jail sentence of five years, compared to civilians who were imprisoned for an average of one or two years. (See video under “Resources”)

The German Democratic Republic (GDR), informally called East Germany by West Germany and other countries, was a socialist state established in 1949 in the Soviet zone of occupied Germany, including East Berlin of the Allied-occupied capital city.

The Berlin Wall was a wall in Berlin, Germany that separated Communist East Berlin from democratic West Berlin. The Wall was erected overnight on August 12-13, 1961. Over the 28 years that the wall was in place, East Germany jailed more than 75,000 people who tried to flee to the West across the Wall, and 809 people died or were killed in escape attempts.

On November 9, 1989, the East German government announced that all GDR citizens could visit West Germany and West Berlin. The wall was finally torn down over the next few weeks.

News was hard to get in communist East Berlin in 1961, unless it was an official government news report. Reuters correspondent Adam Kellett-Long, on assignment in East Berlin, had approached a senior member of the government two days earlier [on Aug. 11, 1961]… and asked him what was going on. He had replied “If I were you and I had plans to spend this weekend away from Berlin, I wouldn’t.” Now it was already Saturday.

Kellett-Long could find nothing of note on the teleprinter of the East German government’s official news agency, ADN. Nothing of note in the early editions of the official newspaper, Neues Deutschland. Midnight passed in a news vacuum, and the story Kellett-Long began to work on for the next news cycle looked like being an anti-climax. Then the phone rang. The man on the line spoke German. “I strongly advise you not to go to bed tonight,” he said, and then hung up without saying who he was.

Then the ADN teleprinter clattered, reeling out a Warsaw Pact communique from Moscow urging “effective control” round West Berlin. Aware that this was the moment he had been waiting for, Kellett-Long rushed out to look for clues to “effective control.”

Outside there was silence and gloom. No sign of a story as he drove towards the Brandenburg Gate, main crossing point to West Berlin. Just as he reached it a Vopo (a policeman) waving a red torch (flashlight) stopped his car and told him he could go no further. “The border is closed,” he said.

As he drove back to his apartment/office to file the momentous story, his car was halted for 10 minutes by a seemingly endless convoy of trucks ferrying heavily-armed militia and police to the East-West dividing line.

While the State Radio began broadcasting a series of ominous decrees to the still sleeping population, all road crossing points as well as the city’s underground and overhead railways also closed. Work began with concrete posts and barbed wire all along the border.

It was the start of the wall which, until the crude cement blocks that formed it could be swung into place, snaked through Berlin as a barbed wire fence, halting the exodus of people from East Germany and ending the daily trek to West Berlin of thousands who earned their living there.

Reuters was eight minutes ahead of everyone in reporting the event, scoring not only through being first but because for a long time no other western journalist was in East Berlin to rival Kellett-Long’s graphic eye-witness story. Border police and troops for a while let no-one pass.

By daylight it was known that westerners would be allowed to cross, but the border was closed to East Germans and West Berliners unless they had a special pass. The Reuters correspondent, using his green press accreditation card, was the first person to drive through the Brandenburg Gate in a car with East Berlin number plates after the clamp-down.

The wall was to be a one-way filter. The refugee exodus was over and Berlin was a divided city. Read Adam Kellett-Long’s report below:

Berlin, August 13, 1961.

Tonight I saw East German Police lob smoke and tear-gas bombs into a crowd of youths who had been mocking and shouting at them at a point half a mile from the border with West Berlin.No one was hurt in this, the most serious incident so far since the border between the East and West sectors was sealed off. The jack-booted police had driven the crowd, about 300 strong, from the border, but the youths were still defying their levelled rifles. Suddenly the police major in charge shouted, “Fire.” The tear-gas bombs flew into the crowd, sending the youths scattering into near-by streets.

Early today I became the first person to drive an East Berlin car through the police cordons since the border controls began shortly after midnight. The clamp-down was in full swing.

The Brandenburg Gate, main crossing point between the two halves of the city, was surrounded by East German police, some armed with sub-machine guns, and members of the para-military “factory fighting groups.”

West Berlin and West German cars were passing freely into East Berlin, in accordance with the new regulations. In contrast to my earlier failure to get through into West Berlin just after the borders had been temporarily sealed, my special green accreditation card this time gained me a free passage from a courteously smiling policeman.

He told me: “Nobody was allowed through for a period of about one hour in the middle of the night while we got in position. Now things are working as we mean them to go on, someone with a card like yours (the ordinary East Berliner has a red card) will not be prevented from going through. But you must take no East Germans with you.”

I drove back through the gate and watched four West Berlin cars pass through after a policeman saluted and checked their identity cards. All asked questions, and he explained the new regulations patiently. It appeared that the police were under strict instructions to try to avoid incidents.

At one of the other 13 checkpoints cars and pedestrians were being allowed through. Three cordons of police checked my passport as I walked through. The first cordon was armed with rifles or sub-machine guns, the second with revolvers and batons. The third group were unarmed. The security precautions nevertheless were on a large scale. All along the border about 100 yards back, armed police and factory workers were guarding buildings in pairs. I sighted one armed policeman gazing out from a top-floor window.

It is hard to see how controls can be kept up at their present rate.

During the rest of 1961, the grim and unsightly Berlin Wall continued to grow in size and scope, eventually consisting of a series of concrete walls up to 15 feet high. These walls were topped with barbed wire and guarded with watchtowers, machine gun emplacements, and mines. By the 1980s, this system of walls and electrified fences extended 28 miles through Berlin and 75 miles around West Berlin, separating it from the rest of East Germany. The East Germans also erected an extensive barrier along most of the 850-mile border between East and West Germany.

In the West, the Berlin Wall was regarded as a major symbol of communist oppression. About 5,000 East Germans managed to escape across the Berlin Wall to the West, but the frequency of successful escapes dwindled as the wall was increasingly fortified. Thousands of East Germans were captured during attempted crossings and 191 were killed.

In 1989, East Germany’s communist regime was overwhelmed by the democratization sweeping across Eastern Europe. On the evening of November 9, 1989, East Germany announced an easing of travel restrictions to the West, and thousands demanded passage though the Berlin Wall. Faced with growing demonstrations, East German border guards opened the borders. Jubilant Berliners climbed on top of the Berlin Wall, painted graffiti on it, and removed fragments as souvenirs. The next day, East German troops began dismantling the wall. In 1990, East and West Germany were formally reunited.

Background

THE BERLIN WALL:

- The Berlin Wall was a wall in Berlin, Germany that separated Communist East Berlin from democratic West Berlin.

- It was one of the most visible symbols of the Iron Curtain.

- The wall was built in 1961 by the government of the German Democratic Republic (East Germany) to stop the tide of emigration to West Berlin.

- Because of dissatisfaction with the economic and political conditions (forced collectivization of agriculture, repression of private trade, supply gaps), an increasing number of people left the GDR. From January to the beginning of August 1961, about 160,000 refugees were counted.

- Armed guards patrolled the eastern side of the wall. In 1962, Peter Fechter was shot while attempting to cross into West Berlin, and slowly bled to death in front of a large crowd, which started a riot and led to Fechter becoming a symbol of resistance against the wall. Onlookers did not attempt to aid Fechter, as they feared the communist guards might fire upon them as well.

- The symbolism of the wall as a representative of the divide between capitalism and communism was not lost on American President Ronald Reagan, who, in a famous 1987 speech, urged Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev to “tear down this wall!” These words proved prophetic, on November 9, 1989 the German Democratic Republic announced that the border would be re-opened. The wall was promptly destroyed.

- In the following year the parliament of the German Democratic Republic voted for reunification and became new states (Bundesländer) of the Federal Republic of Germany.

CONSTRUCTION OF THE WALL:

- The Wall was erected overnight on August 12-13, 1961.

- This was a Saturday night and most Berliners slept while the East German government began to close the border and install barbed wire fences through Berlin.

- The first concrete sections were installed on August 15, 1961, and over the following few months the concrete block sections were extended.

- In June 1962 the wall was further consolidated, and in 1965 the “third generation” of Wall replaced this earlier construction.

- Consisting of concrete slabs between steel girder and concrete posts with a concrete sewage pipe along the top, this was itself replaced in many areas after 1975 with newer concrete segments which were more resistant to breakthroughs.

ESCAPE ATTEMPTS:

- East Germany jailed more than 75,000 people who tried to flee to the West across the Wall, and 809 died in escape attempts.

- Of those who died, 250 were killed at the Berlin Wall itself; 370 died on the border between East and West Germany; and 189 had been trying to get out via the Baltic Sea.

- An average of seven people were jailed every day for trying to get out between 1961 and 1989.

- Many thousands of East German border guards (Grenztruppen, known colloquially as “Grenzers”) also tried to escape, and around 2,500 succesfully made it to the West. However, 5,500 were captured in the attempt and received an average jail sentence of five years, compared to civilians who were imprisoned for an average of one or two years.

- Historians researching the files of the Stasi (East German Secret Police) found that in 1961 the secret police devoted virtually all of their resources and their 50,000 staff solely to stopping people leaving the country. Anyone thought likely to flee was forcibly moved away from border areas. Other people were encouraged to spy on their friends, neighbours and colleagues and inform on them if they were considering an escape.

EAST GERMAN SECRET POLICE (STASI):

- The MfS or Ministerium für Staatssicherheit (German: "Ministry for State Security"), more commonly known as the Stasi, was the official secret police of East Germany.

- As the most comprehensive internal security organization of the Cold War, it was the most effective, and repressive, intelligence and secret police agencies in the world.

- Founded by the Soviets in 1947 and reorganized in 1950, the Stasi's motto was Schild und Schwert der Partei ("Shield and Sword of the Party").

- The Stasi was much larger in East Germany than the Gestapo had been in the Nazi state.

- Like its Soviet model, the Stasi constituted a secret police force, a secret intelligence agency, and an official investigative organ.

- The Stasi systematically infiltrated every part of society, and used hundreds of thousands of secret informers to ensure that ideas [against the government] were immediately identified and rooted out.

- No one trusted anyone outside their family. The Stasi controlled a widespread network of informants, and out of a population of 16 million it is estimated that 400,000 people were active informants.

- The Stasi maintained files on 6 million of its own citizens, more than 38% of the entire population, and all telephone calls and mail from the West were monitored.

- Stasi operatives routinely collected scent samples (Geruchsproben "smell samples") from people by wiping cloth over objects they had touched or by breaking into people’s homes and stealing their dirty underwear, the samples then being stored in airtight containers. The scents were then passed to police equipped with sniffer dogs who could pick the individuals out amid a crowd. People were imprisoned and tortured simply for telling political jokes.

- The Stasi was disbanded 5 months after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989.

(from conservapedia and wikipedia)