Game about Communist rule of Poland

Daily News Article — Posted on May 3, 2013

(by Daniel Michaels, The Wall Street Journal) – WARSAW – Shopping in communist Poland was a dreary ordeal of shortages, rationing lines and – if you managed to buy something – Soviet-Bloc dreck [junk]. So Karol Madaj has turned it all into a board game called Queue.

The challenge: Buy everything on your shopping list. Players wait outside empty government stores, fend off line-jumpers and haggle with black marketeers. The 40-page instruction manual warns the game may inspire “tears of exasperation” and “the gnashing of teeth.”

Queue, introduced in 2011, paradoxically proved to be so popular that buyers had to stand in line for hours for one and a black market emerged.

It also inspired a competing game about frustrations of Polish shopping during the 1980s, called You Cut the Line, Sir. Publisher Jaroslaw Basalyga says his goal was to create a game “whose climate and emotions convey the absurdity of those years.”

Polish kids today don’t know how good they’ve got things. Surrounded by candy, electronics and hipster fashion, they live their parents’ old dreams. So an increasing number of adults – who grew up with “chocolate-like product,” lumpy vinyl “Relaks” footwear and a tiny ration of sanitized Warsaw Pact TV cartoons – are out to tell children how bad things were before Poland shed Soviet domination in 1989. …

Post-communist [teachers] are using children’s books, graphic novels and games to inform young people about life in the People’s Republic of Poland, or PRL as it is known by its Polish initials.

Writer Aneta Gornicka-Boratynska, who was born in 1971, tired of her children saying, “We know you had nothing and we have everything.” So she created a children’s book called “Green Oranges, or the PRL for Children.” It is filled with vintage black-and-white photos and narrated by a colorful cartoon girl who explains phenomena like perennially unripe citrus fruit.

“My son can’t imagine life without Lego,” says Ms. Gornicka-Boratynska, whose first visit to a French hypermarket in 1990 was “like seeing something from another planet.” When she was young, farm women would show up at her mother’s Warsaw office selling black-market meat while government butcher shops had nothing.

“Marzi,” a series of graphic novels, recounts author Marzena Sowa’s childhood in the 1980s. It depicts a child’s-eye view of shortages, strikes and martial law that cracked down on the Solidarity trade union. The books are popular across Europe and have been translated into English. …

The success of “Marzi” has surprised Ms. Sowa, since “it’s not about superheroes.” Ms. Sowa started writing while studying in France, at the urging of her French boyfriend, who found her tales fascinating. He illustrates the books. Ms. Sowa, who was 10 when communism ended, now gets invited to speak to school groups about Marzi. She brings yellowing ration cards to show that the history is real. “Kids don’t know how the story ends,” she says.

Creating a fun way to learn about suffering under communism without making communism seem fun entails walking a fine line – even about rationing lines. Queue creator Mr. Madaj, who was born in 1980, spent a year balancing accuracy and amusement. “The first version was boring and nobody wanted to play it,” he recalls.

Making communism’s waning years seem silly is OK, though, since one Polish defense against Soviet oppression was mockery. An explanation of East Bloc consumerism in the Queue instruction booklet includes a poem about rationing lines with the line, “What are you in line for? Old age.”

Mr. Basalyga, who developed You Cut the Line, Sir for the Polish unit of Denmark’s Egmont Media Group, says that for kids today, “the battle for toilet paper or Soviet electronic games is fun in itself.” The game also prompts children to ask their parents questions about the era, he says.

Maciej Gorski, who was born three years after communism ended and grew up hearing about how bad it was, finds Queue fun because of its nuttiness. “The PRL’s end is an easy target of parody, and we mainly talk about it with a wink of the eye,” says Mr. Gorski, who has also studied more serious history, such as Stalin’s brutal imposition of communism on Poland.

Poles can laugh about the 1980s because communism ended peacefully and Poland has prospered. …

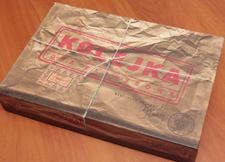

People lined up—with faux (imitation) rationing tickets—to buy Queue, a board game about lining up to buy goods in Soviet-era Poland.

Unintentionally, the game is a living example of that world because it is produced by the Polish government. The Institute of National Remembrance, a state body created in 1998 to preserve memories of Poles’ struggles against Nazism and communism, gets money to produce Queue from the national budget. Overwhelming demand hasn’t induced bureaucrats to fund a production increase.

“It’s like under socialism,” quips Andrzej Zawistowski, the institute’s director of public education, who is pushing for a market-based approach. One queue for Queue formed roughly four days before sales began, he said.

The shortage of the game about shortages has even prompted angry letters from consumers for whom it brought back bad memories, says Mr. Madaj. “Some people didn’t appreciate the irony.”

Copyright 2013 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Reprinted here for educational purposes only. Visit the website at wsj.com.

Questions

1. What was shopping like for Poles living under communist control?

2. What is the object of the board game Queue created by Karol Madaj?

3. What does the competing game You Cut the Line, Sir illustrate?

4. What is the ultimate goal of these games?

5. Describe the irony experienced by Poles trying to buy Queue. Be specific.

OPTIONAL: Send an email to the Polish government's Institute of National Remembrance, which funds the production of Queue to ask whether they plan on selling the board game in English, and if they would consider selling it through an online store.

http://ipn.gov.pl/en/contact

Remember to identify yourself (name, school, state), and note that you read the Wall Street Journal's article about Queue at StudentNewsDaily.com. Be clear, concise and polite.

Background

A BRIEF HISTORY OF POLAND (from the Polish government's Institute of National Remembrance website)

From 1944 to 1989, Poland was under the Communist rule. Despite changes during that period, Poland had no sovereignty though it enjoyed recognition in the international arena. During that forty-five year period, all key decisions regarding both Polish foreign and domestic policies were made in Moscow. At the same time, despite changes brought about by social upheaval in 1956, 1968, 1970, 1976 and 1980, Poland was under totalitarian rule. The scope and character of totalitarian repression was most intense during Stalinist times, which lasted until the mid 1950s.

Poland was not free from political repression also after 1980. Nevertheless, during the 1980s, the Solidarity movement, with its charismatic leader Lech Walesa, came on the political scene. The Communists were not able to hold on to their dictatorship in spite of Martial law imposed on Poland in December 1981. Thousands of Solidarity leaders were arrested. The 'disciplinary forces' brutally put down the strikes in shipyards, factories, steelworks, and coalmines. Workers were killed and wounded. This tragedy is documented by the Institute of National Remembrance.

A few years had passed and the world changed immensely. Unprecedented reforms in the Soviet Union within the Perestoika programme and the politics of the United States which gained a military and technological dominance enabled the Central and Eastern European countries to finally release themselves from the Soviet rule. Poland has long been ready to initiate radical changes which benefited the Polish nation and the whole Central and Eastern European region.

In 1989, as a result of the Round Table negotiations the historical compromise was reached. 'Solidarity' officially entered the political scene. On June 4, 1989 the first free elections to the Senate and partially free - contracted - elections to the Sejm took place. Poles voted against the old political system. Three months later the first independent government headed by Prime Minister Taduesz Mazowiecki was created. It took three further months to change the official name of the state: People's Republic of Poland became history; a free and democratic Republic of Poland was born.