Finland storing nuclear waste 100 stories underground

Daily News Article — Posted on January 27, 2017

(by Zeke Turner, The Wall Street Journal) – OLKILUOTO, Finland – Finland has found what the whole world is looking for: A place to bury their most dangerous nuclear waste. It is 100 stories below ground.

From the U.S. to the U.K., Germany and Japan, plans to dig containers for highly radioactive nuclear fuel rods [nuclear waste] have hit political roadblocks or faced backlash from locals who don’t want toxic waste in their backyards. But Finland has been quietly breaking ground.

On this Baltic Sea island off the Finnish coast, the country’s two main nuclear-power companies have just begun digging the main chambers of a tunnel system they aim to complete by 2020 to safely house 6,500 tons of spent uranium for the next 100,000 years.

But building deep-rock storage bunkers isn’t just a challenge for engineers and scientists. Finland also stands out in how it has managed the project’s tricky politics, using financial incentives to frame the decision to host the site as a boon for locals rather than a perceived threat. …

Around the world, the majority of spent nuclear fuel—which remains radioactive for thousands of years—is stored in cooling pools at reactor sites or, once cooled, in steel casks sheathed in concrete. But neither method is a long-term fix, industry experts and advocacy groups say. The pools, which are filling up, can break down over decades, and both methods have raised concerns about the high costs and adequacy of security to protect them from disasters or potential attacks.

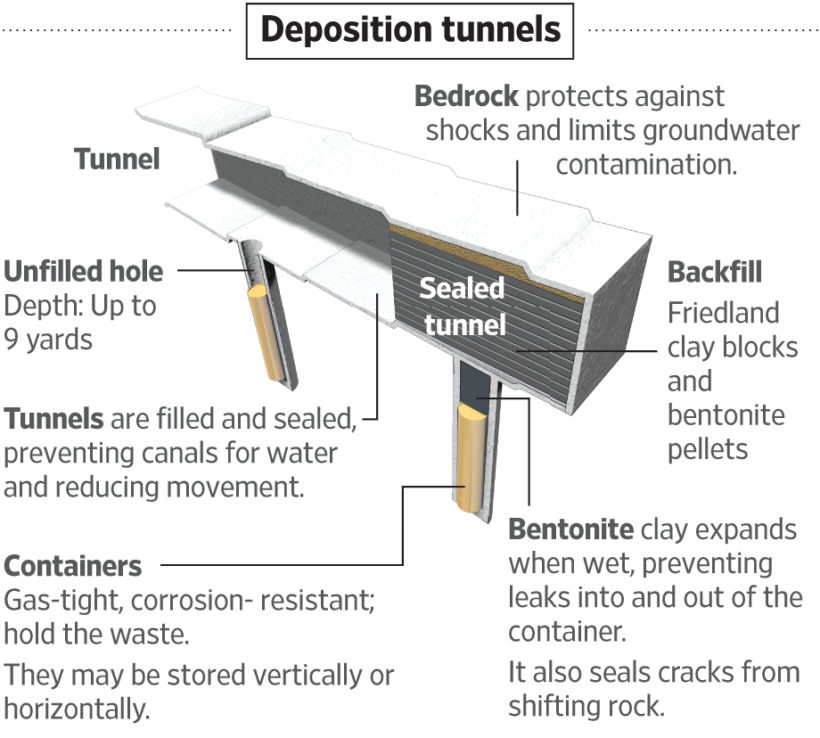

Scientists largely agree that deep-in-the-earth burial sites are the safest way to dispose of the most dangerous radioactive waste, though finding the right geological conditions can be expensive and time-consuming. Once the spent fuel rods are meticulously buried inside, these high-tech underground tunnel systems are backfilled and sealed shut. …..

Hans Forsström, senior adviser at SKB International, the consulting arm of Swedish nuclear waste-management company Svensk Kärnbränslehantering AB, said the Finnish plans were carefully designed “in a way that it won’t affect the people on the surface.”

“To get their trust is the difficult part,” he said.

Under a nuclear law passed in 1987, Finnish counties that host nuclear sites were given veto power to stop projects. This sent the message that no community would be forced to host a bunker. Then, the Finnish nuclear-waste company announced in 1992 that it was considering five potential sites. Politicians in those municipalities were left competing over who would get to host the project and collect property taxes from the company, according to Matti Kojo, an expert on Finland’s nuclear policy at the University of Tampere.

The municipality of Eurajoki, whose Olkiluoto Island is the site of two of Finland’s nuclear plants, won by offering the most land to the waste company and reasoning that the majority of Finland’s radioactive waste was already stored temporarily there. Construction of the site began in 2004. …..

Researchers in Finland are constructing a massive underground tomb for nuclear waste. When nuclear fuel is no longer useful for generating power, it is still dangerously radioactive for thousands of years. The Onkalo facility is designed to store this waste for at least 100,000 years.

Meanwhile, the nuclear plants and the repository have come to reap the municipality €16 million ($17.2 million) in annual real-estate tax revenue from the nuclear industry—a hefty sum, given Eurajoki’s total budget of €65 million.

That tax injection has eased many of the concerns Eurajoki’s 9,300 residents may have once had over hosting the site. Between 1984 to 2008, the percentage of residents who thought that nuclear fuel rods couldn’t be stored safely underground dropped from 60% to 34%, according to a survey by Mr. Kojo of the University of Tampere.

The money has paid for a new library, a senior home, two day-care centers, hiking trails, a hockey rink, a Finnish baseball field, and renovations for local schools and a historical mansion owned by the municipality. It also allowed the municipality to levy income tax at 18%, the third-lowest in Finland.

Now politicians and nuclear-power operators elsewhere are looking to Eurajoki for inspiration. “From Japan, we have had I don’t know how many delegations…maybe hundreds,” said Jorma Aurela, the chief engineer in Finland’s ministry of economic affairs.

But Finns say their remedy doesn’t only boil down to purchasing local acquiescence. Jussi Heinonen, the director of the Nuclear Waste and Material Regulation department at Finland’s nuclear-safety regulator Säteilyturvakeskus, or STUK, says Finns’ high level of trust in industry experts and the government sets the country apart.

Finland never experienced the political backlash against nuclear power that has long plagued Germany, where protests in the 1970s gave rise to the country’s Green party. In 2011, after the Fukushima disaster, Chancellor Angela Merkel decided to phase out nuclear power in the country by 2022.

“Finnish people—maybe it is the weather outside—we are very practical,” said Pasi Tuohimaa, a spokesman for the Finnish utility Teollisuuden Voima Oyj, or TVO.

Lawmakers in Germany have given themselves until 2031 to find a place to dig, and U.S. scientists are waiting to see whether the Trump administration will revive the Yucca mountain project or start a new search altogether.

Meanwhile, the ballooning global stockpile of spent nuclear fuel—266,000 tons of spent uranium fuel were in temporary storage at the end of 2015, according to the International Atomic Energy Agency in Vienna—risks billions in costs for taxpayers and companies until final waste storage is built.

“The technological solutions are largely in place, which is shown by the Finns,” said Irina Gaus, the director of research and development at Switzerland’s National Cooperative for the Disposal of Radioactive Waste. “Society has to decide how to deal with the waste.”

Reprinted here for educational purposes only. May not be reproduced on other websites without permission from The Wall Street Journal. Visit the website at wsj .com.

Background

Politics often block [nuclear waste storage] projects before the digging begins.

- Plans for the U.S.’s Yucca Mountain facility, 90 miles from Las Vegas, for instance were stalled in 2010 by then-Nevada Sen. Harry Reid, who strangled the project’s funding in spending bills. The now-retired Democratic Senate leader called the rods “the most poisonous substance known to man."

- A German plan to use the country’s Gorleben salt mine as a storage site was derailed after federal politicians in Berlin failed to get local approval behind the project, a political third rail. In Japan, the government spent years asking communities to host sites before giving up and asking scientists to make a shortlist.

- And after a county council rejected in 2013 a burial site for highly radioactive waste in Cumbria in northwestern England, the U.K. is starting from scratch canvassing 13 regions of Wales, England and Northern Ireland for volunteers to host a site in what a spokesman for the U.K.’s Radioactive Waste Management office called “a community-led process.” (from the WSJ article above)

NUCLEAR POWER IN THE U.S.

- In 1979, an accident occurred at the Three Mile Island (TMI) nuclear plant near Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. Although no one was injured and no harmful levels of radioactive emissions were released, the operating utility nearly went bankrupt paying for the cleanup.

- After the incident, public opinion turned solidly against the nuclear power industry. Nuclear power was dealt an additional blow in 1986 when a terrible accident at the Chernobyl plant in the Soviet Union killed 31 people immediately and exposed an estimated 4,000 more to high doses of radiation.

- Containment vessels built around American reactors are designed to be an ultimate safeguard against any incidents. The vessel at Three Mile Island worked as designed; but tragically, Chernobyl, built under far lower safety standards than are the norm in western countries, had no such last line of defense.

- Advances in technology offer the possibility that future reactors can be made inherently safe from meltdown, but existing reactors of older design will remain in operation for many years. While the U.S. industry has taken steps to reduce the possibility of human error, some analysts argue that accidents due to operator mistakes are inevitable.

- Potentially, the biggest problem with nuclear power is the management and disposal of the tons of radioactive wastes produced every year. Nuclear plants produce far less waste than do coal plants. A 1,000-MW nuclear-electric plant, for example, produces about one metric ton of waste per year, versus one million tons from a similarly sized coal plant. However, nuclear waste is far more dangerous.

- Many of the waste products are highly toxic and remain radioactive anywhere from less than one year to millions of years. On the other hand, toxicity is generally inversely proportional to half-life, and some scientists argue that after about 1,000 years most of the waste would be no more dangerous than uranium ore.

- Further complicating the storage problem is that the wastes initially generate large amounts of heat. Spent fuel currently is stored at the plants in pools of water that absorb the radiation and dissipate the heat. Heat produc- tion drops quickly as the wastes age.

- Geological isolation is the only viable long-term disposal solution currently available. This means storing the wastes in highly stable geologic formations that have remained seismically inactive…

- Such formations exist both on land and beneath the oceans, but transporting spent fuel to these sites must be done with care. Terrorists could try to sabotage storage sites or, more likely, attack convoys hauling the materials.

- The so-called NIMBY (Not In My Back Yard) syndrome is just as important as are the geological issues in locating a suitable site for waste disposal. Not surprisingly, people are reluctant to live near a nuclear waste dump.

- Billions of dollars have gone into building a permanent storage facility for high-level radioactive wastes at Yucca Mountain, Nevada. The facility, run by the Department of Energy, was to have opened in 1998, but the project is behind schedule. Even after construction is complete, however, political opposition from Nevada’s citizens and politicians may keep the facility’s doors shut.

(from instituteforenergyresearch.org/pdf/bradley/Bradley_ch_2_1.pdf, or go to instituteforenergyresearch.org and type “Using Energy” in search box).