Battle of Coral Sea 75th anniversary

Daily News Article — Posted on May 5, 2017

(by Ruth Brown, New York Post) – On Thursday, surviving veterans from the U.S. and Australia met with President Trump and Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull on board the USS Intrepid in New York to finally give the little-known WWII Battle of the Coral Sea the recognition it deserves, at a gala dinner hosted by the American Australian Association.

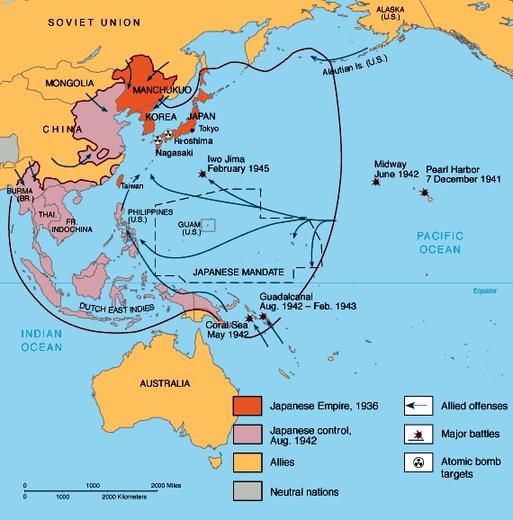

Most people are familiar with the Battle of Midway which occurred a month later, where the allies first inflicted a major blow against the Japanese, but it was Coral Sea was where the tide first started to turn, according to the association’s president, former ambassador to Australia John Berry. “It was an ugly war, but we were on the offensive. It shifted from defense to offense at the Coral Sea,” said Berry.

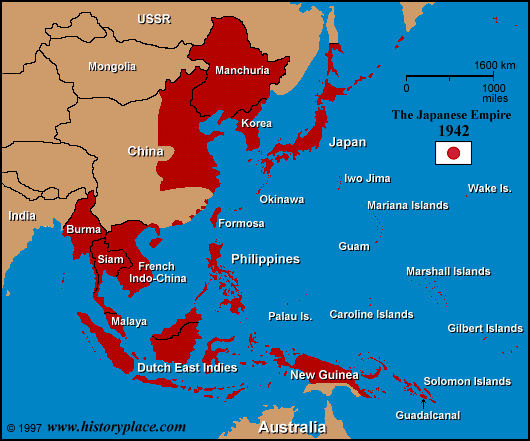

Until that point, Japan seemed unstoppable. It had already toppled Hong Kong, Singapore and Malaya, and the Aussies had just intercepted communications that Japanese forces were about to invade New Guinea.

Australia was sure to be next.

With the British Royal Navy’s regional forces decimated from earlier battles, and the rest of its troops tied up fighting Hitler in Europe, Adm. Chester Nimitz, commander in chief of America’s Pacific Fleet, answered the Aussies’ SOS without a second thought.

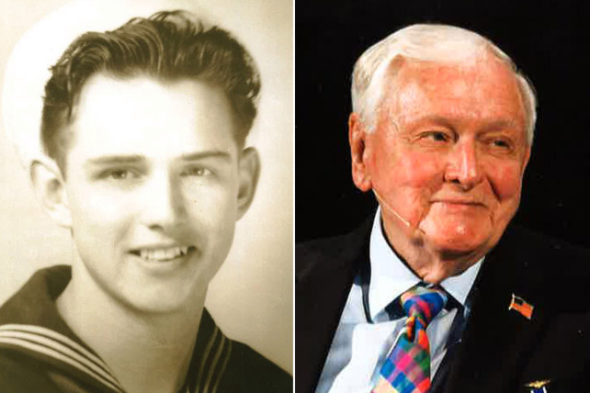

“The captain told us this was an English country, these are our English counterparts,” recalls John Hancock, 92, then just 17 and a Georgia kid fresh from the farm serving aboard the Yorktown. “They were trying to keep supply lines open to Australia.”

Nimitz deployed two US carrier groups — one with the USS Yorktown, the other with the USS Lexington — while Australian Rear Adm. John Crace commanded a joint support force that included two Aussie cruisers, the HMAS Australia and HMAS Hobart.

[Thursday’s event was almost certainly the last major commemoration to be attended by those who fought in one of the great sea battles of World War II that also re-defined the nature of naval warfare.The Battle of the Coral Sea was fought entirely by aircraft attacking ships; the opposing ships did not make visual contact or exchange direct fire at any time.

The air-sea battle was contested between May 4 and May 8, 1942. It came about after the Japanese dispatched an invasion fleet to take Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea in early May, 1942. They also sent a carrier force to patrol into the Coral Sea to intercept any American carriers sent to thwart their planned attack. The Japanese landed at Tulagi in the Solomon Islands on May 2 as their invasion fleet, protected by carrier air support, headed towards Port Moresby on the south coast of Papua.

The Allies had cracked the main Japanese codes and deciphered Japanese radio messages. This enabled an American carrier force, supported by Australian cruisers and destroyers, to wait and intercept the invaders after Admiral Nimitz had ordered his two available carrier groups, Rear Admiral Frank Fletcher’s Task Force 17, built around USS Yorktown and Rear Admiral Aubrey Fitch’s Task Force 11, centred on USS Lexington, into the Coral Sea.

The Allied group was under the command of Rear Admiral Fletcher of the United States Navy. Rear Admiral John Crace commanded the Australian heavy cruisers Hobart and Australia in the joint taskforce.]

The two sides began dueling from a distance on May 4, but the real battle began on May 7, when US planes discovered a Japanese light carrier and tore it apart in a hail of bombs and torpedoes, killing 638 Japanese fighters.

The Japanese exacted some damage of their own, taking out a US oiler and a destroyer, but their attempts to sink Crace’s force were largely a bust, thanks to the Aussies’ fearless defense.

The two Australian cruisers skillfully outmaneuvered the onslaught while their men blasted back into the skies.

“The captain drove the Hobart like a Formula One motor car to dodge the torpedo and bombs,” Gordon Johnson, then a 19-year-old, recently told the national daily The Australian.

“They strafed the ship with machine guns, and along with our anti-aircraft guns and the whine of the turbines, the noise was extraordinary. It was like putting your head in an empty 44-gallon drum and someone whacking it with a hammer.”

The next morning, the battle reached its brief, bloody climax as both sides discovered and attacked their counterparts’ most valuable assets: the carriers.

The Americans hit first, sending out 75 aircraft that did serious damage to an enemy carrier, but the flyboys struggled to see the other boats, which were obscured by bad weather.

Then the Japanese hit back, and suddenly, the Americans were in the thick of battle.

“I fired at the Japanese planes, like everybody else did, [but] who knows who was shot and who was hit,” Hancock recalls. “I fired about five canisters — and there are 250 rounds in a canister.”

…The Yorktown came out relatively unscathed — it had dodged eight torpedoes and was hit by only a single bomb. But 66 men were killed or seriously injured.

The Lexington — the slower of the two carriers — fared worse. Its captain evaded five torpedoes but two found their target, sparking a fire that tore through the ship. [The Lexington lost 216 men, but thousands made it out alive.]

The craft remained afloat for the battle but was ultimately too damaged to continue, and the crew abandoned ship before it was scuttled. …

The Allies didn’t actually win the battle — Tokyo considered it a tactical victory because its forces had sunk the largest ship — but they did enough damage to take Japan’s newest carriers out of commission, which proved to be a decisive advantage at Midway.

And it introduced our naval leaders to the new realities of warfare on the seas.

“This was the first naval sea battle where the ships never see each other — they were five hours apart by sea, 20 minutes by air. The devastation that’s wrought by air shows everybody that naval warfare has totally changed,” says Australia’s John Berry.

Coral Sea also halted Japan’s advance toward Australia — and it is something the Aussies have never forgotten.

[Over four days more than 70 aircraft and ships were destroyed, but the Japanese advance south was successfully halted and the prospect of an invasion of Australia ended.More importantly, it was the first time the Japanese had been halted during their southwards advance across the Pacific.]

Reprinted here for educational purposes only. May not be reproduced on other websites without permission from the New York Post.

Questions

1. Where exactly is the Coral Sea?

2. a) When did the Battle of the Coral Sea take place?

b) What countries took part in this battle?

c) Which U.S. aircraft carriers were involved in the battle?

3. Name the U.S. and Australian commanders involved in the battle.

4. How was this battle fought?

5. What was the outcome of the Battle of the Coral Sea?

6. What was the significance of this battle?

7. Newsreels were short films covering current events, shown in movie theaters before the movie. They contained filmed news stories and items of topical interest. Newsreels were prevalent between 1910s to 1960s, when TV news replaced the need for them.

Watch the newsreel (and the short documentary below it) on the Battle of the Coral Sea. The tone of the newsreel on the Battle of the Coral Sea is very different from the tone of news reporting today.

a) Do you like this style of reporting? Explain your answer.

b) How would you describe the naval cameraman who continued to film from the deck of the carrier during the attack by the Japanese?

c) After watching the second video (the Australian account), how important do you think it is for students to learn about this battle?

Background

The Battle of the Coral Sea was a tactical victory for the Imperial Japanese Navy - they lost fewer resources - but a strategic victory for the U.S.Navy. We stopped the planned Japanese invasion of Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea. Japanese Imperial Army units slated for this operation were diverted to Guadalcanal, where they were consumed in the battle of attrition there. (from a commenter at usmilitaryforum)

The Allied force had 128 carrier aircraft and the Japanese had 127 carrier aircraft:

- U.S. Task Force 11 included the USS Lexington, commanded by Rear-Admiral Fitch. Task Force 11 consisted of USS Lexington (carrier), Minneapolis (heavy cruiser), New Orleans (heavy cruiser), Phelps (destroyer), Dewey (destroyer), Farragut (destroyer), Aylwin (destroyer) and the Monaghan (destroyer)

- U.S. Task Force 17 included the USS Yorktown, commanded by Rear-Admiral Fletcher, together with protective cruisers and destroyers. Task Force 17 consisted of USS Yorktown (carrier), Astoria (heavy cruiser), Chester (heavy cruiser), Portland (heavy cruiser), Hammann (destroyer), Anderson (destroyer), Russell (destroyer), Walke (destroyer), Morris (destroyer) and Sims (destroyer)

- Australian Task Force 44 commanded by the Australian Rear-Admiral Crace and consisting of a group of Allied warships, including the heavy cruiser HMAS Australia and the light cruiser HMAS Hobart whose target was the Japanese Port Moresby Invasion Group

- The Japanese force included the aircraft carriers ‘Shokaku’, the ‘Zuikaku’ and the 'Shoho'. The Japanese attack on Port Moresby, codename ‘Operation MO’, was important as its success would isolate Australia and New Guinea and could then be used as a platform to attack Samoa and Fiji. Port Moresby was a key city on the southern coast of New Guinea.

(from american-historama .org)