Australian doctors perform pioneering heart transplants

Daily News Article — Posted on November 3, 2014

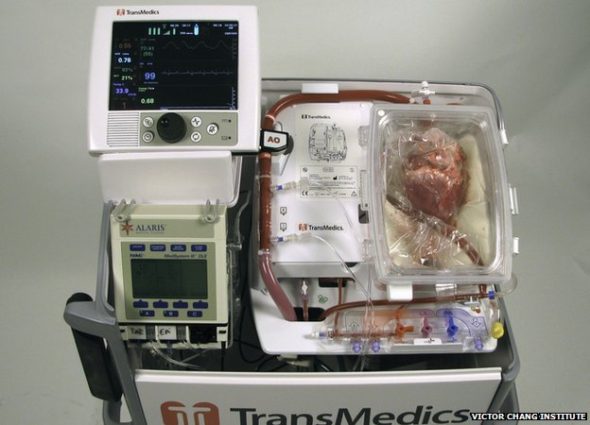

The console where the heart is “reactivated” is being called the heart-in-a-box machine

In what’s being hailed as a major medical breakthrough, surgeons in Australia have successfully performed the first-ever “dead heart” transplants–replacing patients’ failing hearts with donor hearts that had stopped beating for an extended period of time before transplantation.

A team at St. Vincent’s Hospital in Sydney revived and then transplanted hearts that had stopped beating for up to 20 minutes. Until this breakthrough, the heart was the only organ that was not used after it stopped functioning (stopped beating) – known as donation after circulatory death. Beating hearts are normally taken from brain-dead people, kept on ice for around four hours and then transplanted to patients.

To enable this to happen, scientists developed an organ care machine, known as the “heart in a box,” which connects the “dead” heart to a circuit that restores the heart beat and keeps it warm. (Once inside, the heart is restarted, preserved and can be monitored before the transplant operation.)

The “heart in a box” – a portable device developed by Andover, Massachusetts-based TransMedics, revives a no-longer-beating heart while warming it and perfusing it with oxygenated, nutrient-rich blood. During this process, the organ is injected with a preservation solution that helps keep heart cells from dying to ensure that the organ survives surgery.

“Both the preservation solution and the console allow the heart to be kept warm and beating and have blood going through it and getting oxygen,” according to Dr. Bob Graham, executive director at the Victor Chang Cardiac Research Institute in Australia, which developed the preservation solution. “Both of them are extremely important and I think if either had come alone, we would have a slight improvement but we wouldn’t have been able to do what we’ve done.”

The preservation solution, which alone took 12 years to develop, minimizes damage to the organ after it has stopped beating and helps ensure it both survives the surgery and functions in the recipient’s body. It also makes the heart more resilient to the transplant process as well as improving heart function when it is restarted.

Two of the patients who received the new hearts in Sydney beamed as they spoke to reporters last week.

Michelle Gribilar, a 57-year-old grandmother from Sydney who suffered from congenital heart failure, became the first person to undergo the procedure two months ago. She said she now “feels like she is 40.” Before the surgery, she couldn’t walk more than 100 meters at a time. “I’m a different person altogether. Like I walk almost 2 miles a day, I go up the stairs, about 120 to 100 stairs a day,” she said.

“It’s a wild thing to get your head around, that your heart’s (come from) a stranger, someone you don’t know — part of them is now inside you,” said another recipient, Jan Damen. “It’s a privilege. It’s an amazing thing.”

The new procedure may have advantages because living hearts are generally stored on ice, which can cause damage.

“The first heart transplant that we did looked very, very poor indeed,” Dr. Graham said. “By the time they put it into the patient it was looking very good. Several weeks after the transplant, they did a biopsy of the heart and they did an echocardiogram to look at the function of the heart and they were…virtually completely normal.”

Experts say the procedure could save the lives of 20 to 30 per cent more heart transplant patients. The procedure will allow far more hearts to be made available for transplants, including from donors whose organs are donated after circulatory death [DCD].

“In all our years, our biggest hindrance has been the limited availability of organ donors,” said Dr. Peter MacDonald, head of St. Vincent’s heart transplant unit.

“Up until now no-one’s attempted to recover hearts from these donors [whose hearts have stopped beating] to transplant them. In some other jurisdictions, in the UK for instance, about 40 per cent of their donors are DCD donors so we think it has enormous potential impact.”

Transplants involving other DCD (circulatory death) organs such as kidneys, livers and lungs are already widely accepted. Similar methods of warming and nourishing these organs before transplant have been used to improve the quality of lung and liver transplants.

The researchers have been developing the heart procedure for about 20 years.

Compiled from news articles from London’s Daily Telegraph, BBC News, Sky News, Huffington Post and CNN.

Questions

1. What breakthrough has been made with heart transplants? How has it changed the way heart transplants are done?

2. Describe how the “heart in a box” organ care machine works.

3. What is the benefit of the preservation solution used in the “heart in a box”?

4. What problem do recipients have when receiving “living” hearts for transplants?

5. a) How many more people’s lives can potentially be saved because of this breakthrough?

b) Why is this the case?

6. What two adjectives would you use to describe your reaction to this news story? Explain your answer.

7. This scientific breakthrough may help to address a dilemma regarding heart donation.

An ethical dilemma is faced with heart donation, in the fact that the heart must be removed from a person before it stops functioning/beating in the body—but after the person has been declared “brain dead.”

Defining death as “brain death,” even though the heart is still beating, presents ethical quandaries.

Robert D. Truog, MD, director of clinical ethics at Harvard Medical School in Boston, Mass., writes that using brain death as the standard legitimatizes organ removal from bodies that continue to have circulation and respiration (many times sustained by mechanical ventilation), and this "fails to correspond to any coherent biological or philosophical understanding of death."

When do you think death occurs: a) Only once the heart stops beating, or b) When either the heart stops beating OR when a person is declared brain dead. Explain your answer.

Have something to say about this article? Send a Letter to the Editor at: editor@studentnewsdaily.com. (Click here for guidelines.)