Who Will Be the First American Counted in the Census? It Came Down to Two.

Human Interest News — Posted on December 2, 2019

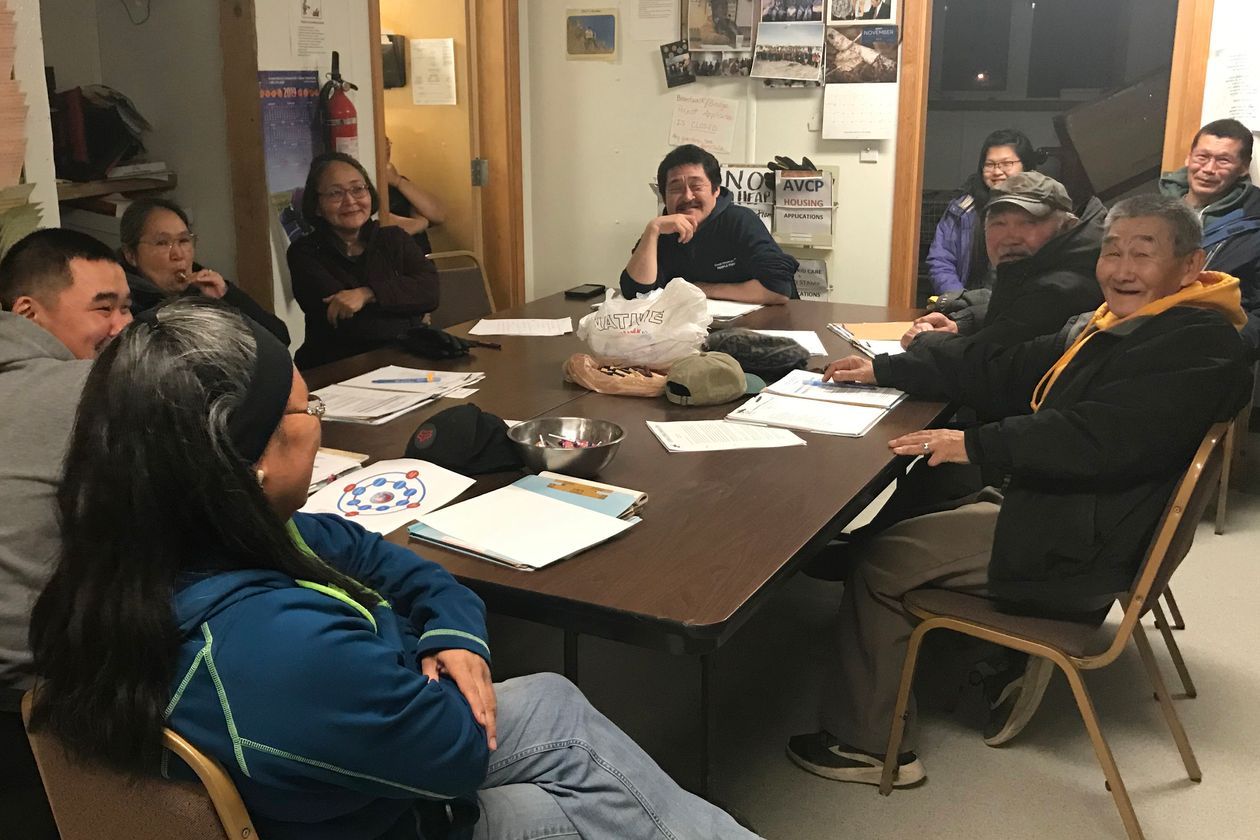

(by Janet Adamy, The Wall Street Journal) – TOKSOOK BAY, ALASKA — In this tiny coastal village, five leaders of the Nunakauyarmiut tribe huddled around a table one recent evening to make a decision: Who will be the first person counted in America for the 2020 census?

They wanted to pick the oldest resident of this 659-person fishing outpost. Two of them, Alois Lincoln and Lizzie Chimiugak, both seemed to be 89 years old—but the records aren’t exactly clear on their birthdates.

“They guessed back then,” resident Charles Moses said as he watched the debate unfold.

In the coming decennial count, the government will ask most Americans to respond online for the first time, starting shortly before Census Day on April 1. The count really kicks off in January, however, in remote parts of Alaska—where internet is spotty and some homes lack addresses. There, census takers must count every household by hand.

Alaska starts early because residents are more likely to be home during winter’s peak, and frozen terrain is easier to cross than the mushy ground of spring. On Jan. 21, specially trained enumerators with paper and pencils (because ink can freeze) will start knocking on tens of thousands of doors.

The director of the Census Bureau, Steven Dillingham, will personally count the first resident in this tight-knit community on Nelson Island, a mass of tundra in the Bering Sea at the state’s southwestern edge that’s accessible only by plane and boat. Its dirt roads are lined with low-slung houses that overlook the water, and residents still catch herring, hunt musk-ox and pick berries to eat.

That picturesque scenery—coupled with a gravel airstrip and a school principal willing to let census visitors sleep on classroom floors—helped it get picked as the starting place for the count. The Census Bureau started designating a single remote village to launch the count in 2000, letting residents pick who was counted first.

Mr. Lincoln, a former elementary school janitor who had 11 children, appeared first in line for Toksook Bay’s oldest resident. Tribal officials say records at their office show he was born Jan. 1, 1930.

Alois Lincoln is one of Toksook Bay’s oldest residents. (Photo: Janet Adamy/The Wall Street Journal)

Mr. Lincoln’s family casts doubt on his official birthdate, logged nearly three decades before Alaska became the 49th state.

Priscilla Moses, a daughter of Mr. Lincoln, said a vital records official in Juneau once called with surprising news: that he was really born on Oct. 16, 1929, which would make him 90. Neither date rings true to Mr. Lincoln. “I don’t feel like I’m that old,” he said.

The discrepancy likely stems from the fact that Catholic missionaries who settled the area recorded baptismal dates in place of birth dates, or possibly used the terms interchangeably, locals say.

Ms. Chimiugak, a locally renowned Eskimo dancer and mother of 12, considers her birthday Jan. 20, 1930. Yet one tribal official said Ms. Chimiugak’s records list a baptismal date of Jan. 10 of that year, and indicate she may have been 1 year old then. That would make her at least 90.

Lizzie Chimiugak holds a pair of her traditional boots in Toksook Bay. (Photo: Janet Adamy/The Wall Street Journal)

Ms. Chimiugak recalled playing with Mr. Lincoln when they were young and described him as like “my little brother.” Asked if she thinks she’s the oldest person in the village, she said, “I don’t know.”

Some residents questioned whether the calendar is the right guide for the decision. “Is it by age, or by their wisdoms?” asked Simeon John, a longtime inhabitant. “It could go either way.”

Mr. Lincoln grew up in Tununak, a coastal village to the north, and moved his entire house by sled to Toksook Bay after it became a burgeoning fishing hub in 1964. Besides working as a janitor, he set up a small shop to sell sweets, and spent his free time carving earrings from the tusks of walruses until deteriorating vision forced him to stop. Now he plays bingo a few times a week, and spends afternoons at Ms. Moses’ house.

Ms. Chimiugak, who was born in a nearby village and moved here with her late husband in the mid-1960s, became known as a mentor who passes down the local culture and Yugtun language, the village’s indigenous tongue. At the annual dance festival, she tells the audience how residents used to behave (for instance: young sweethearts never held hands in public). Her technique for making mak’aq, a creamy dessert of mashed fish eggs, seal oil and salmonberries, was featured in the Village Telegraph in August.

At the meeting over the decision early this month, Thomas Julius, the council president, thought going in that Mr. Lincoln was the logical choice because he appeared to be the oldest.

Members of the Nunakauyak Traditional Council meeting on Nov. 5 to decide the first person counted in the 2020 census. (Photo: Janet Adamy/The Wall Street Journal)

Joseph Asuluk Sr. felt Ms. Chimiugak was a better pick because she’s a proven public speaker. “She shares more knowledge than Alois,” he said.

Mr. Julius proffered a compromise. “Can we pick both of them?” he asked. A few heads nodded at that idea. Others pointed out that one person would ultimately need to go before the other. For a while, everyone fell silent.

Lucy Therchik chimed in to say that she, too, felt Ms. Chimiugak was better suited to the role. Anyone visiting for the start of the count might have questions. “She would have the answers,” Ms. Therchik said.

Joseph Henry, another participant, agreed. Mr. Julius felt the tide of the room moving toward Ms. Chimiugak. He saw their point. “Alois,” he said. “He’s shy.”

The next afternoon, council office clerk Winnie Julius walked into Ms. Chimiugak’s home and found her nestled on her couch watching TV. Her wispy silver hair was pulled back from her face to reveal an earring dangling from her left lobe, one of Mr. Lincoln’s walrus tusk creations.

Ms. Julius leaned in close as she delivered the news that Ms. Chimiugak would be the first person counted in the coming census, a day after she celebrates her birthday. Ms. Chimiugak nodded her head. “I understand what the census means,” she said. “I’m happy.”