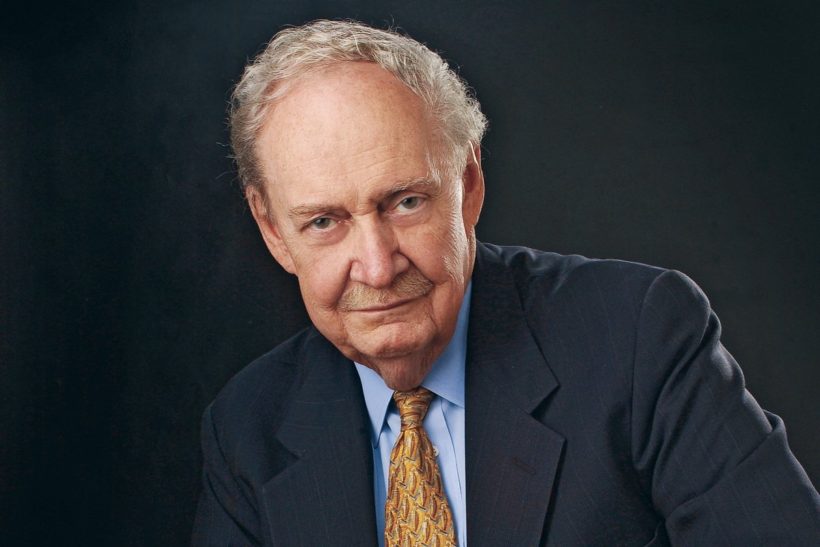

Robert Bork in 2011

The following is an excerpt from OpinionJournal’s “Best of the Web” at WSJ written by the editor, James Taranto.

Bork to the Future

Remember Robert Bork? If you do, you’re not a member of the New York Times editorial board. Justice Antonin Scalia’s death over the weekend at 79 prompted the Times’s editors to drop Bork (who died in 2012) down the memory hole:

When Antonin Scalia was named by President Ronald Reagan to fill a vacancy on the Supreme Court in 1986, the Senate considered the nomination for 85 days, then voted to confirm him. The tally was 98-0.

That unanimity was by no means a measure of widespread agreement with Justice Scalia’s judicial philosophy. Rather it was the Senate’s customary acknowledgment—at least until recently—that the president had fulfilled his constitutional duty and selected a clearly qualified person for the post.

Thirty years later, and within hours of the news that Justice Scalia had died, Senate Republicans, led by Majority Leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky, rejected that practice outright.

Here is what McConnell said, in a statement Saturday: “The American people should have a voice in the selection of their next Supreme Court Justice. Therefore, this vacancy should not be filled until we have a new President.”

The Associated Press reports that Sen. Ron Johnson of Wisconsin agrees. So does Sen. Kelly Ayotte of New Hampshire, in a Sunday statement, and the Times reports that Sens. Rob Portman of Ohio and Pat Toomey of Pennsylvania have signed on as well, “leaving nearly every vulnerable Republican incumbent backing Mr. McConnell’s pledge.”

The Times editorialists assert that “the latest Republican talking point is that for 80 years it has been ‘standard practice’ not to confirm any Supreme Court nominee in an election year.” That, they claim, is “untrue—Justice Anthony Kennedy was confirmed by a Democratic Senate in 1988.” Which is true, if barely. Kennedy, nominated in 1987, was confirmed Feb. 3, 1988, and sworn in 28 years ago this Thursday.

The Times leaves out everything that happened between Scalia’s confirmation and Kennedy’s—and a lot more to boot. We thought we’d review the relevant history.

The Senate website has a list of all high-court nominations formally submitted to the upper chamber since the First Congress in 1789. It is true that there have been periods in which the Senate acted more or less as a rubber stamp. One such period lasted from 1930, after the narrow rejection of Judge John Parker, a Hoover nominee, through 1965, when Abe Fortas was confirmed as an associate justice. During that period, the Senate confirmed 23 justices, 17 of them by voice vote (i.e., with no recorded opposition); and no nominee received more than 17 “no” votes.

There were no vacancies in 1966, so that the modern era of Supreme Court politics began in 1967, just under half a century ago. It is an era in which the Senate has been increasingly assertive in using its power to reject or block nominees to the high court—and, more recently, to lower courts as well. Usually it has been Democrats who’ve been at the forefront in developing and using hardball tactics to weaken the presumption of deference to the president. Herewith a timeline:

1967. Johnson’s nomination of Judge Thurgood Marshall, the great civil-rights lawyer, met resistance from Southern Democrats anxious to preserve white supremacy. “He was confirmed 62-11, but it wasn’t really a wide victory,” historian Wil Haygood, author of a book on the Marshall nomination, said in an interview last year:

By the rules of the Senate, the southern senators were only eight votes short of a filibuster. President Johnson was able to convince twenty southern segregationists to not vote, which was amazing because senators lived on their votes. For Lyndon Johnson to twist the arms of twenty other southerners was really quite amazing.

1968. In June, Chief Justice Earl Warren announced his intention to retire—the last vacancy before this weekend to arise in a lame-duck president’s final year. Johnson sought to elevate Justice Fortas to the center seat and named Judge Homer Thornberry to succeed Fortas. “The president took encouragement from indications that his former Senate mentor, [Georgia Democrat] Richard Russell, and Republican Minority Leader Everett Dirksen would support Fortas, whose legal brilliance both men respected,” according the Senate website.

But Fortas lost Russell’s support “because of administration delays in nominating his candidate to a Georgia federal judgeship.” And the confirmation hearings didn’t go well:

Those hearings reinforced what some senators already knew about the nominee. As a sitting justice, he regularly attended White House staff meetings; he briefed the president on secret Court deliberations; and, on behalf of the president, he pressured senators who opposed the war in Vietnam. When the Judiciary Committee revealed that Fortas received a privately funded stipend, equivalent to 40 percent of his Court salary, to teach an American University summer course, Dirksen and others withdrew their support. Although the committee recommended confirmation, floor consideration sparked a filibuster.

Johnson withdrew the nominations a month before Election Day.

1969-70. Although the Senate remained under Democratic control, Richard Nixon’s nomination of Warren Burger was easily confirmed. Meanwhile, another Fortas money scandal arose, and he resigned from the court in May 1969. Nixon appointed Judge Clement Haynsworth to replace him. As the Times reported in Haynsworth’s 1989 obituary:

Labor and civil rights groups, citing what they denounced as unfavorable rulings, fought the Haynsworth nomination while the Nixon Administration waged a strenuous campaign of cajoling and arm-twisting to win the Senate’s approval.

The battle pitted the Nixon Administration and conservative Republicans who favored Judge Haynsworth against the A.F.L.-C.I.O., the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights, an alliance of 125 religious, labor, welfare and civil rights groups.

The Senate rejected Haynsworth’s nomination, 55-45, with 38 Democrats and 17 Republicans in opposition.

Nixon’s next nominee, Judge G. Harrold Carswell, fared no better. He too drew ideological opposition from liberal interest groups, and was also said to be “mediocre.” That prompted Sen. Roman Hruska’s memorable declaration: “Even if he were mediocre, there are a lot of mediocre judges and people and lawyers. They are entitled to a little representation, aren’t they, and a little chance?” The Senate voted Carswell down, 51-45. Nixon’s third choice, Harry Blackmun, was confirmed unanimously in May 1970, almost a year after the seat became vacant. In 1973 he gave us Roe v. Wade .

1971. Twenty-six senators, 23 of them Democrats, voted against William Rehnquist’s confirmation as an associate justice. Their primary objection was to a memo Rehnquist had written two decades earlier, as a law clerk to Justice Robert Jackson, defending the constitutionality of segregation. Rehnquist said the memo reflected Jackson’s views, not his own, although Jackson ultimately voted with the rest of the court in Brown v. Board of Education .

1986. When Chief Justice Burger retired, Reagan nominated Justice Rehnquist to replace him and Scalia to take Rehnquist’s seat. Although Scalia was confirmed unanimously by the Republican Senate, Rehnquist faced a replay of his 1971 confirmation battle. This time a majority of Democrats, 31, voted “no” (along with two Republicans, both of whom had voted “yes” 15 years earlier). The Civil Rights Monitor observed at the time:

The Rehnquist nomination received the most negative votes of any successful Supreme Court nominee in this century. (Rehnquist holds second place also, for the 26 negative votes cast when he was first nominated to the court in 1971.)

1987. Here is the case the Times memory-holed. Justice Lewis Powell retired at the end of the term in June, and Reagan nominated Judge Robert Bork to succeed him. Although the Democrats had taken the Senate majority in the 1986 election, Bork looked like a safe pick. No one doubted his qualifications, and the Senate Judiciary Committee’s chairman, Joseph Biden of Delaware, had said: “Say the administration sends up Bork and, after our investigations, he looks a lot like Scalia. I’d have to vote for him, and if the groups tear me apart, that’s the medicine I’ll have to take.”

“That was before Biden heard from liberal groups,” observed George Will. Also before he heard from Sen. Edward Kennedy, who delivered this famous harangue, quoted in NPR’s Bork obit: “Robert Bork’s America is a land in which women would be forced into back-alley abortions, blacks would sit at segregated lunch counters, rogue police could break down citizens’ doors in midnight raids, and schoolchildren could not be taught about evolution.”

The New York Times was fully behind the left’s ideological assault on Bork. In October the paper editorialized:

The President’s supporters insist vehemently that, having won the 1984 election, he has every right to try to change the Court’s direction. Yes, but the Democrats won the 1986 election, regaining control of the Senate, and they have every right to resist. This is not the same Senate that confirmed William Rehnquist as Chief Justice and Antonin Scalia as an associate justice last year.

That view prevailed. Later that month the Senate rejected Bork’s nomination, 58-42, with only two Democrats voting “yes.” Most Southern Democrats—now dependent on the black vote—opposed Bork, who was depicted as a foe of civil rights.

At length Reagan nominated Judge Kennedy (no relation to Teddy). Linda Greenhouse—then the Times’s Supreme Court correspondent, now an acknowledged opinion writer—inked a Week in Review piece with the triumphant title “With the Kennedy Nomination, the Center Holds.”

Kennedy was the last Supreme Court nominee to be confirmed unanimously.

1990-91. The Senate remained under Democratic control during the presidency of George H.W. Bush. In 1990 his first high-court nominee, Judge David Souter, was relatively uncontroversial (and on the bench turned out to be a lockstep liberal). But even he drew nine “no” votes from Democrats.

But then came Justice Marshall’s retirement and Bush’s nomination of Judge Clarence Thomas. Again, liberal interest groups mobilized, and a majority of Democratic senators (along with two Republicans) announced their opposition. But Thomas was black, so several Southern Democrats who’d rejected Bork felt it necessary to back Thomas. A last-ditch effort to smear him by leaking allegations of verbal ribaldry from his confidential FBI background investigation succeeded in switching only three Democratic votes—among them that of Harry Reid, now minority leader.

Thomas was confirmed 52-48. Rehnquist’s record of 33 noes had been shattered after just five years.

1993-94. Both of Bill Clinton’s high-court appointments came during his first two years in office, when Democrats held the Senate majority. Only three Republican senators voted against Judge Ruth Bader Ginsburg and nine against Judge Stephen Breyer. Notwithstanding Democrats’ treatment of Haynsworth, Carswell, Rehnquist, Bork and Thomas, Republicans largely adhered to the tradition of assenting when a Democratic president “had fulfilled his constitutional duty and selected a clearly qualified person for the post.”

2003-04. There were no Supreme Court vacancies in George W. Bush’s first term, but after Republicans took the Senate majority by a bare 51-49 margin in the 2002 election, the Democratic minority began using the filibuster to block nominees to federal appellate courts, with an eye toward scuttling potential high-court nominees. (At this point, thanks to Democrat-initiated reforms dating to the 1970s and unrelated to controversies over judicial nominations, ending a filibuster required 60 votes.)

As the Washington Examiner’s Timothy Carney noted in 2013, an aide to Sen. Dick Durbin, now the Senate’s No. 2 Democrat, emailed the senator that one of the blocked nominees, Miguel Estrada, was “especially dangerous, because he has a minimal paper trail, he is Latino, and the White House seems to be grooming him for a Supreme Court appointment.”

2005-06. Having expanded their Senate majority in 2004 to 55-45, Republicans became increasingly frustrated with the Democrats’ filibustering of judges. They considered employing what was dubbed the “nuclear option”—changing Senate rules during the session to abolish the 60-vote requirement. That effort was abandoned when a bipartisan group of 14 senators, inevitably dubbed a “gang,” agreed to preserve the filibuster while limiting its use for the remainder of the congressional term. Estrada had already withdrawn his nomination, but several other blocked nominees made it onto the appellate bench.

Then two Supreme Court seats became vacant in quick succession, with Sandra Day O’Connor’s retirement and Rehnquist’s death. Judge John Roberts was confirmed as chief justice, 78-22—these days a wide margin for a Republican nominee in a Democratic Senate. But Alito won only four Democratic votes (and lost one Republican), for a final tally of 58-42.

There was a futile effort to block Alito by filibuster. By a vote of 72-25 his nomination was allowed to proceed to the floor. Among those who would have denied him a vote was then-Sen. Barack Obama, along with Biden and Hillary Clinton.

2007. The Democrats retook the Senate in 2006, and Sen. Chuck Schumer of New York—a Judiciary Committee member and Reid’s heir-apparent as Democratic leader—laid down a marker, as Politico reported:

Schumer . . . said Friday the Senate should not confirm another U.S. Supreme Court nominee under President Bush “except in extraordinary circumstances.”

“We should reverse the presumption of confirmation,” Schumer told the American Constitution Society convention in Washington. “The Supreme Court is dangerously out of balance. We cannot afford to see Justice [John Paul] Stevens replaced by another Roberts, or Justice Ginsburg by another Alito. . . .

Schumer said there were four lessons to be learned from Alito and Roberts: Confirmation hearings are meaningless, a nominee’s record should be weighed more heavily than rhetoric, “ideology matters” and “take the president at his word.”

2009-10. Justices Souter and Stevens retired with Democrats holding both the White House and the Senate majority. That meant both nominees were easily confirmed—but for a change, over considerable Republican opposition. Thirty-one senators voted against Judge Sonia Sotomayor, 37 (including one Democrat) against Elena Kagan.

2013. The Democrats, still holding the Senate majority and frustrated with Republicans’ use of the filibuster, invoked the “nuclear option” by a 52-48 vote. Now all judicial (as well as executive) nominations can be approved by simple majority—except for the Supreme Court. Pro-abortion groups reportedly commanded Democrats to maintain the filibuster as an option to block a future Republican president’s high-court nominations.

So: Senate Democrats tried to filibuster a Supreme Court nominee in 1967, applied ideological tests against plainly qualified nominees starting in 1971, both used and abolished the filibuster against lower-court nominees when it suited their purposes, and argued nine years ago for reversing “the presumption of confirmation.” Somehow they never prepared for the possibility of a Supreme Court vacancy under a Democratic president and a Republican Senate. But then, this is the first time that’s happened since 1895.

As is their wont, progressives are trying to drum up a sense of crisis to get their way. “Scalia’s Death Plunges Court, National Politics Into Turmoil,” a Washington Post headline claims. Slate warns of a “constitutional crisis” if the Senate fails to defer to the president. Brent Staples, a New York Times editorialist, even tries to reopen the Civil War: “In a nation built on slavery, white men propose denying the first black president his Constitutional right to name Supreme Court nominee,” he asserted in a Saturday tweet, deleted in the face of widespread mockery.

We know the recipe. It’s two parts pure applesauce, one part argle-bargle and a dash of jiggery-pokery. There is no constitutional crisis, but at most a political one of the sort that has arisen repeatedly over the past half-century. The country is not in turmoil; it’s just the usual Obama-era ugliness. And slavery was abolished by the 13th Amendment, a constitutional provision even many progressives are willing to respect as written.

Republicans shouldn’t have any trouble preventing Obama from replacing Scalia during this congressional term. The big question is: Can they win the political argument over the future of the Supreme Court?

Who knows? But consider what Ted Cruz said on the subject in Saturday’s debate:

We are one justice away from a Supreme Court that will strike down every restriction on abortion adopted by the states. We are one justice away from a Supreme Court that will reverse the Heller decision, one of Justice Scalia’s seminal decisions, that upheld the Second Amendment right to keep and bear arms.

We are one justice away from a Supreme Court that would undermine the religious liberty of millions of Americans and—and the stakes of this election, for this year, for the Senate, the Senate needs to stand strong and say “We’re not gonna give up the U.S. Supreme Court for a generation by allowing Barack Obama to make one more liberal appointee.”

Contrast that with Hillary Clinton’s remarks on the court in a Feb. 3 town hall:

Well, I’ll tell you what, Dave. I do have a litmus test. I have a bunch of litmus tests because I agree with you. The next president could get as many as three appointments. You know one of the many reasons why we can’t turn the White House over to the Republicans again is because of the Supreme Court.

I’m looking for people who understand the way the real world works, who don’t have a knee-jerk reaction to support business, to support the idea that, you know, money is speech, that gutted the Voting Rights Act.

I voted for the reauthorization of the Voting Rights Act when I was in the Senate. It passed 98 to nothing based on a very extensive set of hearings and research. Supreme Court comes along. They substitute their judgment for the Congress, signed by George W. Bush.

That is one of our problems. They have a view that I just fundamentally disagree with about what the way we have to keep the balance of power in our society is.

So they have given way too much power to corporations. They have given Citizens United, the biggest gift to the Koch brothers, Karl Rove and all of those folks whose values I don’t share, and who are doing everything they can to try to turn the clock back.

We have to preserve marriage equality. We have to go further to end discrimination against the LGBT community. We’ve got to make sure—we’ve got to make sure to preserve Roe v. Wade, not let it be nibbled away or repealed. We’ve got work to do, and here’s how I think about it, because when I was a senator, I had to vote on Supreme Court justices.

I’m looking for people who are rooted in the real world, who know that part of the genius of our system, both economic and government, is this balance of power. If it gets too far out of whack, so that business has too much power, any branch of the government has too much power, the delicate balance that makes up our political system and the broad-based prosperity we should be working for in our economy is the worse off for it.

So I have very strong feelings about what I’ll be looking for if I am given the honor of appointing somebody to the Supreme Court.

Unlike, say, Donald Trump, Mrs. Clinton is trained as a lawyer. Yet the best she can manage when asked about the Supreme Court is a fog of incoherent blather. That may suggest she doesn’t have a winning argument.

For more “Best of the Web” click here and look for the “Best of the Web Today” link in the middle column below “Today’s Columnists.”