The following is an excerpt from OpinionJournal’s “Best of the Web” at The Wall Street Journal written by the editor, James Taranto.

It’s Always in the Last Place You Look

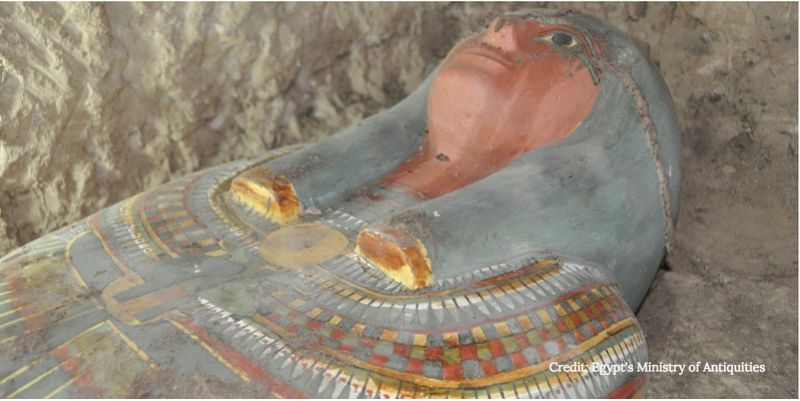

“3,000-Year-Old Mummy Found in Egyptian Tomb”—headline, Seeker .com, Nov. 14

How Did She Lose?

How could Hillary Clinton have lost, and to Donald Trump no less? Lots of explanations are floating around, any combination of which could be right—after all, many factors influence voter decisions.

One excuse from Team Clinton has a ring of plausibility, and that is the FBI. There’s no way to know if James Comey’s Oct. 28 notification that he was reopening the criminal investigation into Mrs. Clinton’s illicit private email server was the turning point, but it felt like one. The New York Times reported Sunday that in a conference call with donors, the erstwhile nominee opined that Comey’s subsequent “clearing” of her, two days before the election, didn’t help:

Mrs. Clinton said a second letter from Mr. Comey, clearing her once again, which came two days before Election Day, had been even more damaging. In that letter, Mr. Comey said an examination of a new trove of emails . . . had not caused him to change his earlier conclusion that Mrs. Clinton should face no charges over her handling of classified information.

Her campaign said the seemingly positive outcome had only hurt it with voters who did not trust Mrs. Clinton and were receptive to Mr. Trump’s claims of a “rigged system.” In particular, white suburban women who had been on the fence were reminded of the email imbroglio and broke decidedly in Mr. Trump’s favor, aides said.

We’d like to suggest two somewhat counterintuitive theories of our own, one involving Trump; the other, his Republican detractors.

Our first theory is that Trump’s manifest weaknesses as a candidate blinded the Clinton campaign to his strengths—the same effect they had had on his Republican rivals in the primary. Stolen emails published by WikiLeaks showed that people in Mrs. Clinton’s inner circle were eager to go up against Trump because they thought he was unelectable.

“We need to be elevating the Pied Piper candidates”—including Trump, Ted Cruz and Ben Carson—“so that they are leaders of the pack and tell the press to [treat] them seriously,” declared an unattributed April 2015 strategy memo quoted by RedState’s Brandon Morse in an Oct. 8 post.

Depending on your point of view, most of Trump’s weaknesses can be seen as strengths. He’s bumptious? He’s self-confident. He says outlandish things? He tells it like it is and isn’t afraid to be politically incorrect. He doesn’t know much about policy? He’s not bound by the Washington consensus that has produced dubious results.

It’s probably true that Trump would have benefited from some restraint. Imagine if he had forborne from picking fights with Judge Gonzalo Curiel, Khizr Khan and Alicia Machado (Miss Universe 1997). As Peggy Noonan suggested, he might have won in a landslide. Still, he won.

Our second theory is that the Nevertrump movement led the Clinton campaign to overestimate its ability to draw Republican voters, and thus to neglect independents and the Democratic base. Trump drew more opposition from the Republican political class than any GOP nominee since at least 1964. But according to the exit polls, he still attracted the votes of 90% of self-identified Republicans, to just 7% for Mrs. Clinton.

Here’s an example: In May, this column lightheartedly identified what we called “the Boot bloc, after Max Boot of the Council on Foreign Relations. These are lukewarm Republicans hotly opposed to Trump—to the point that, as Boot told Vox in March, they would vote for Mrs. Clinton over him.”

Boot, a foreign-policy hawk, responded on Twitter in the same facetious spirit: “@jamestaranto claims there is something called the ‘Boot Bloc.’ Who knew?” But the Clinton campaign evidently took the idea seriously. In August it released an adfeaturing a denunciation of Trump from none other than Max Boot! As we recall, the same Boot clip was part of a video featured at the Democratic National Convention the preceding month. We’ll bet it went over well with Bernie Sanders delegates.

One reason Mrs. Clinton lost is that her sex turned out to be much less of an advantage than her campaign had expected. In particular, her performance among white women was not appreciably better than that of any of the preceding three Democratic nominees. Blogger Kyle Olson notes that on MSNBC the other day, Jess McIntosh, the campaign’s communications director, attributed that to “internalized misogyny,” which, she helpfully explained, “is a real thing.”

Even host Chris Hayes didn’t know what she was talking about, so he prompted her to explain:

“We as a society react poorly to women seeking positions of power. We are uncomfortable about that and we seek to justify that uncomfortable feeling because it can’t possibly be because we don’t want to see a woman in that position of power,” McIntosh said.

“As we go through these numbers, as we figure out exactly what happened with turnout, it seems to be white college-educated women,” she continued.

“We have work to do talking to those women about what happened this year and why we would vote against our self-interest,” McIntosh said.

“Misogyny,” which means hatred of women, seems a strong word to describe this. But let’s stipulate that it is “a real thing”—that there exist women who are “uncomfortable” with the idea of a female president. It seems likely, however, that their number is quite small—and considerably smaller than the number of women who would like to see a female president.

The sensible thing for a female candidate’s campaign to do about voters (women or men) who are averse to a female president would be to ignore them. They’re unlikely to be won over. The swing voters would be the far larger group who are positive about or indifferent to the idea of a female president but have misgivings about the particular candidate. The objective would be to give those voters reasons to support Mrs. Clinton other than (or in addition to) her sex. The notion that voting for a man and against a woman is ipso facto “against [women’s] self-interest” is ridiculous and insulting.

Slate’s Jamelle Bouie—who a year ago described Trump as a “moderate Republican”—has a more sweeping theory: Trump voters are just bad people. We do not exaggerate; his latest piece, published yesterday, is titled: “There’s No Such Thing as a Good Trump Voter: People voted for a racist who promised racist outcomes. They don’t deserve your empathy.”

That sort of identity politics worked out well for Democrats in 2008 and 2012. At the young-adult website Vox, Ruy Teixeira argues it will work again:

Here’s one way to think about the 2016 election. We are witnessing a great race in this country between demographic and economic change that’s driving a new America, and reaction to those changes. On November 8, with a tremendous burst of speed, reaction to change caught up with change and surpassed it.

But is that advantage sustainable over the long haul, as change continues and reaction has to run ever faster simply to keep pace? Probably not. Those old legs will give out eventually, though we do not know exactly when. In the end, the race will be won by change—as it always is.

The last statement is tautological, and the dichotomy between “change” and “reaction” is a false one. By “change,” Teixeira means “change I like,” and by “reaction,” he means “change I dislike.”

Or perhaps, respectively, “change I anticipated,” and “change I failed to anticipate.” Teixeira is co-author, with John Judis, of the 2002 book “The Emerging Democratic Majority”—now available in hardcover from Amazon for 1 cent plus shipping—which put forth the argument that demographic change made Democratic ascendancy inevitable.

In that book, Judis and Teixeira evaluate each state’s presidential prospects “in the next decade.” Using 270towin .com and Photoshop, we mapped them out using the conventional color scheme (and ignoring their further gradations of “competitive” and “very competitive”:

In some ways they got it right. Except for Indiana in 2008, all the “solid Republican” states have lived up to that billing. The West Coast, most of the Northeast and Illinois have proved to be “solid Democratic.” Except in 2004, so has New Mexico. But they made some big errors as well—all in the Democrats’ favor except Colorado and Virginia.

They dramatically overestimated Democratic prospects in both the Upper Midwest and Appalachia. Six states that Bill Clinton carried twice—Arkansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Missouri, Tennessee and West Virginia—have gone Republican in the last four elections and except Missouri were reckoned “solid GOP” in almost all this year’s election maps.

Then there’s the Upper Midwest/Great Lakes region. Trump carried four of the Judis-Teixeira “solid Democratic” states—Iowa, Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin—along with “lean Democratic” Ohio.

While demographic changes may eventually move Texas from “solid” to “lean” GOP, it hasn’t happened yet. And bellwether Florida still leans ever so slightly Republican.

In all, we’d say Judis and Teixeira were about half right. They correctly predicted that nonwhite voters would improve Democratic prospects in states like Colorado, Nevada, North Carolina and Virginia—but they failed to anticipate the scope of Republican gains in other states.

The latter trend probably can’t take the GOP much further; Maine, Minnesota and New Hampshire are the only obvious opportunities Trump didn’t realize this year. It’s certainly possible that the former trend will continue, as Teixeira now predicts, and the emerging Democratic majority will finally emerge.

Or it could recede again. Trump improved slightly over Mitt Romney’s performance among blacks, Hispanics and Asian-Americans—and there’s still plenty more room for improvement.

For more “Best of the Web” from The Wall Street Journal’s James Taranto click here.